Build a Serverless S3 Explorer with Dash

S3 is a great way to store your data in AWS, and it has many integrations with other services. That’s great - as long as you have access to the AWS account. At some point in your journey, especially when building data-driven applications, your business users will want to access data in the bucket, usually reports. Giving all business users direct access to the AWS account and having them navigate the AWS console is generally not feasible or advisable. Today, we’ll build a frontend that business users can use to explore and interact with data in S3 using a separate authentication mechanism.

I should mention that this post is sort of the alpha version of the app; in a later post, we’ll add a more advanced authentication option - Cognito - and add some more quality of live improvements. This builds on the Serverless Dash architecture I introduced in two previous posts. I suggest you check them out if you’re interested in more details:

- Deploying a Serverless Dash App with AWS SAM and Lambda

- Adding Basic Authentication to the Serverless Dash App

As usual the code for all of this is available on Github - check it out.

Before we focus too much on the frontend, there’s one thing we should take care of in the SAM app to improve our developer experience. If you’ve tried to run sam build in one of the other two code bases, you will have noticed that the process is quite slow. That’s because SAM copies every single file from the dependencies into another directory and later compresses it. For Python, there is no way to avoid that when using ZIP-based deployments. Even if you put your dependencies in a separate layer, the copying operation happens every time. SAM offers a more intelligent option for some JS-based Lambdas, but then you’d have to write Javascript. To be fair, this is usually not that big of a deal; it’s just that Dash comes with lots of tiny files, and copying them takes a while - even with a fast machine.

Fortunately, image-based Lambdas exist, and Docker has a more elegant caching mechanism that is able to only do work if stuff changes. Let’s convert our frontend function to an image-based Lambda. This is what the template.yaml looks like after our changes:

# template.yaml

Resources:

FrontendFunction:

Type: AWS::Serverless::Function

Properties:

PackageType: Image

Events:

# ...omitted events for previty

# ...omitted policies for brevity

Metadata:

DockerTag: frontend-function

DockerContext: ./frontend

Dockerfile: Dockerfile

# ...

By default, SAM uses the PackageType Zip, and we need to change that to Image. Additionally, we have to add a Metadata section to tell SAM how to build our image. The DockerTag helps avoid ambiguity in a shared Elastic Container Repository, and the DockerContext basically points to the path where our code is stored, it’s more or less equivalent to the previous CodeUri in the function properties. The Dockerfile key is optional; here, we tell it explicitly that the build instructions are stored in a file called Dockerfile. This is what that looks like:

# frontend/Dockerfile

FROM --platform=linux/amd64 public.ecr.aws/lambda/python:3.12

COPY requirements.txt ${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}

RUN pip3 install -r requirements.txt --target "${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}" --no-cache-dir

COPY . ${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}

CMD ["app.lambda_handler"]

It’s based on the official Python 3.12 Lambda base image, copies the requirements.txt into the container, then installs the dependencies, and only afterward adds the rest of the Python files. Last, it tells Lambda where the entry point for our function is. This setup has the benefit that the dependencies will only be reinstalled if the content of the requirements.txt changes at some point. The initial sam build won’t be very fast, but subsequent builds should finish in a matter of seconds (unless we change the requirements.txt) because it can build on top of a cached layer.

I also added a .dockerignore, which you can think of as a .gitignore for the docker build process. It skips Mac-specific files and the Python cache.

# frontend/.dockerignore

__pycache__

.DS_Store

With all this preamble out of the way, we can finally focus on the app. To make it easier to build a not-awful-looking website, I installed the dash-bootstrap-components which give us access to a variety of components from the bootstrap frontend framework. This will make styling and building the app easier.

# frontend/requirements.txt

boto3

dash==2.15.0

dash-bootstrap-components==1.5.0

apig-wsgi==2.18.0

As preparation for the future, I decided to build a multi-page Dash app. That has become easier in more recent versions, and I suggest you start that way if you plan to build anything beyond the most basic apps. To do that, we first update our build_app function.

# frontend/dash_app.py

def build_app(dash_kwargs: dict = None) -> Dash:

dash_kwargs = dash_kwargs or {}

app = Dash(

name=__name__,

use_pages=True,

external_stylesheets=[dbc.themes.BOOTSTRAP, dbc.icons.BOOTSTRAP],

**dash_kwargs,

)

app.layout = html.Div(

children=[

render_nav(),

dash.page_container,

],

)

return app

I’ve added the CSS for Bootstrap and the use_pages parameter to the constructor. In the basic layout, you can see that the top-level div now has a dash.page_container, which will display the currently active page. Above that, I’m calling render_nav, which renders our navbar.

# frontend/dash_app.py

def render_nav() -> dbc.Navbar:

page_links = [

dbc.NavItem(children=[dbc.NavLink(page["name"], href=page["relative_path"])])

for page in dash.page_registry.values()

]

nav = dbc.Navbar(

dbc.Container(

children=[

*page_links,

dbc.NavItem(

dbc.NavLink(

"tecRacer",

href="https://www.tecracer.com/",

external_link=True,

target="_blank",

)

),

]

),

class_name="mb-3",

dark=True,

)

return nav

The navigation is built on top of bootstrap components and will dynamically add all pages that it finds in the page registry. Let’s talk about that next. The idea behind a multi-page app is that you add your Python modules for the individual pages in the pages/ directory (frontend/pages/ in our case) and have them register themselves as a page.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

import dash

import dash_bootstrap_components as dbc

from dash import html, Input, Output, State, callback, MATCH

dash.register_page(__name__, path="/", name="S3 Explorer (alpha)")

def layout():

"""

Called by Dash to render the base layout.

"""

return dbc.Container(

children=[

dbc.Form(

children=[

dbc.Label(

"Select a bucket to explore",

html_for="select-s3-bucket",

className="text-muted",

),

dbc.Select(

id="select-s3-bucket", options=[], placeholder="Select a bucket"

),

]

),

html.H4("Bucket Content", className="mt-2"),

html.Div(id="bucket-contents"),

],

)

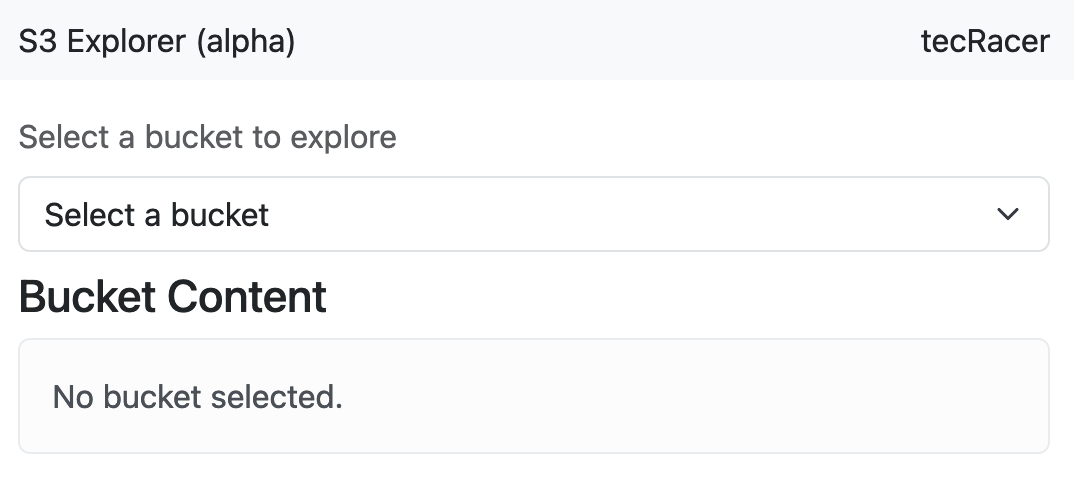

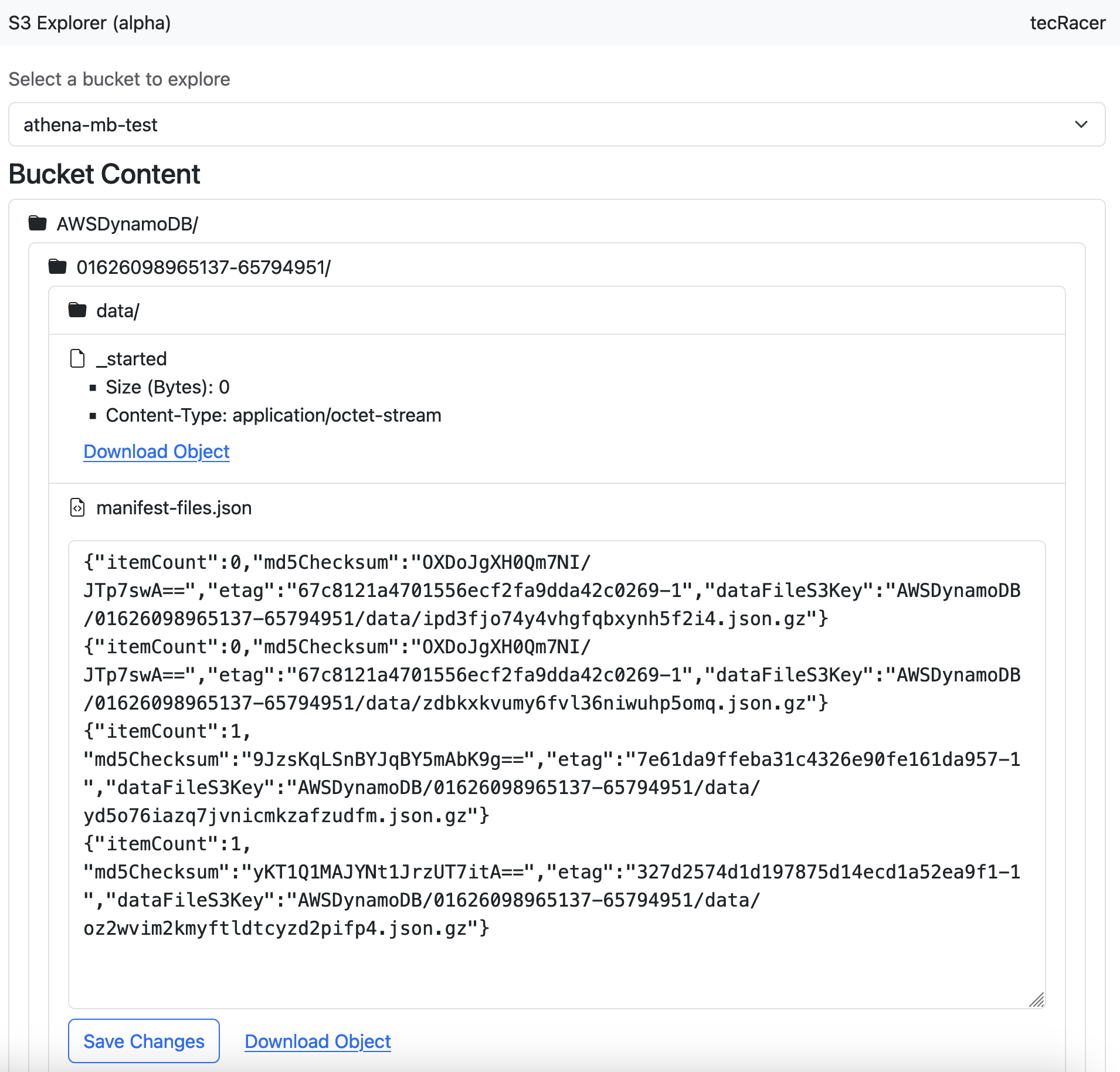

The result of the layout function will be placed beneath the navigation; in our case, it’s just a form with a dropdown to select the S3 Bucket and a few placeholders for the content. When the page is rendered, we need to populate the select box with all available S3 buckets. For this kind of interaction, we create a callback function.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

@callback(

Output("select-s3-bucket", "options"),

Input("select-s3-bucket", "id"),

)

def populate_s3_bucket_selector(_select_children):

s3_client = boto3.client("s3")

bucket_list = s3_client.list_buckets()["Buckets"]

options = [{"label": item["Name"], "value": item["Name"]} for item in bucket_list]

return options

We tell our callback that the result of the function call should be put into the options attribute of our select box, and we also specify an input so our callback gets executed. The id of the select box is not going to change, but our callback will fire once on page load anyway. The function itself uses the regular S3 API to list all buckets, formats the result a bit so Dash can handle it, and returns it. At this point I should probably note that the permission you need is called s3:ListAllMyBuckets as opposed to the name of the API call. This is what it looks like so far.

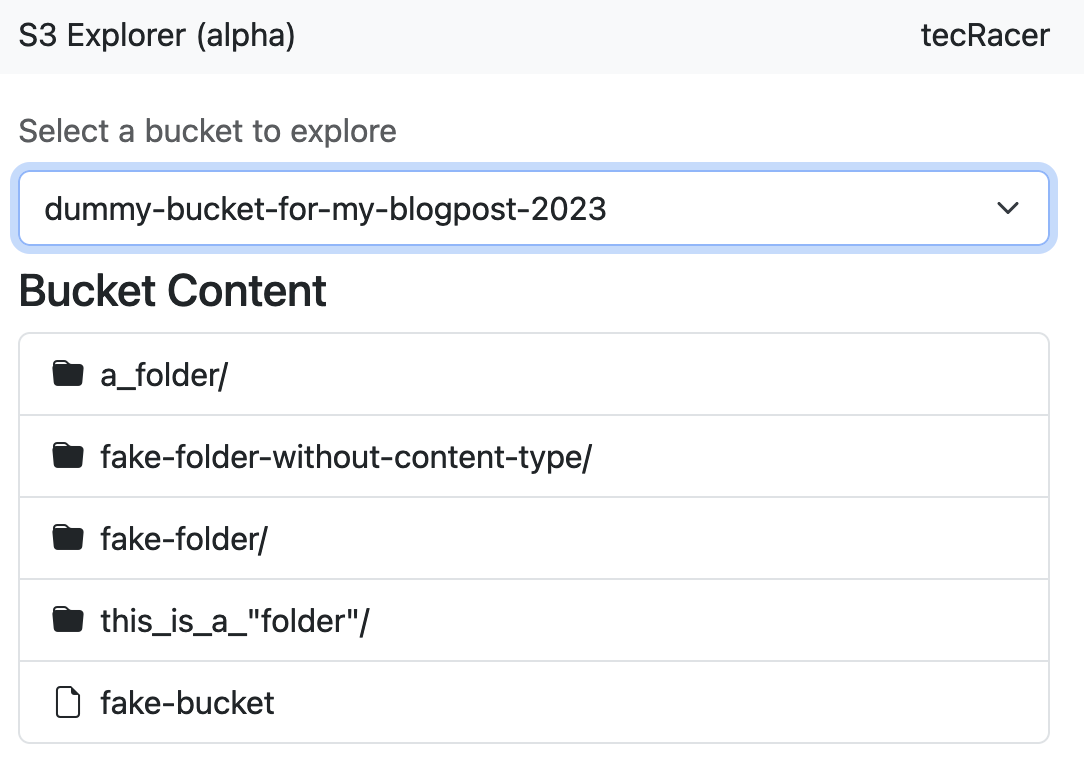

Whenever a user changes the selected button, we want to render the content of that button, so we need another callback that manages that. Here, you can see the handler for this event; it’s triggered whenever the value of the select changes and displays the output as part of our bucket-contents div from the layout function above. If the bucket selection is empty, we render a note letting the user know why they aren’t seeing anything. Otherwise, we return the result of render_directory_listing for the root of the S3 bucket.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

@callback(

Output("bucket-contents", "children"),

Input("select-s3-bucket", "value"),

)

def handle_bucket_selection(bucket_name):

"""

Executed when a bucket is selected in the top-level dropdown.

"""

if bucket_name is None:

return [dbc.Alert("No bucket selected.", color="light")]

s3_path = f"s3://{bucket_name}/"

return render_directory_listing(s3_path)

The render_directory_listing function does most of the heavy lifting in our app, if we can call it heavy lifting. Like the AWS console, it uses the ListObjectsV2 API to get a list of objects and common prefixes on a given S3 path.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

def render_directory_listing(s3_path: str):

# Note: strictly speaking we'd have to check the content type, but this is good enough

is_directory = s3_path.endswith("/")

if not is_directory:

return render_s3_object_details(s3_path)

bucket_name, key_prefix = _s3_path_to_bucket_and_key(s3_path)

s3_client = boto3.client("s3")

list_response = s3_client.list_objects_v2(

Bucket=bucket_name,

Delimiter="/",

Prefix=key_prefix,

)

common_prefixes = [obj["Prefix"] for obj in list_response.get("CommonPrefixes", [])]

items = [obj["Key"] for obj in list_response.get("Contents", [])]

all_items = common_prefixes + items

list_items = [

render_directory_list_item(f"s3://{bucket_name}/{item}") for item in all_items

]

if not list_items:

# Nothing to show

return dbc.Alert("No objects found here...", color="light")

return dbc.ListGroup(list_items, class_name="mt-1")

This function is written so it can handle arbitrary S3 paths (e.g., s3://bucketname/object/key). It first checks if the path ends in a slash. If that’s not the case, it assumes the path refers to an object and renders it as such. Otherwise, as mentioned above, it uses the list objects API to get a list of all objects and common prefixes at this level, which is then rendered to create the next level in the listing hierarchy.

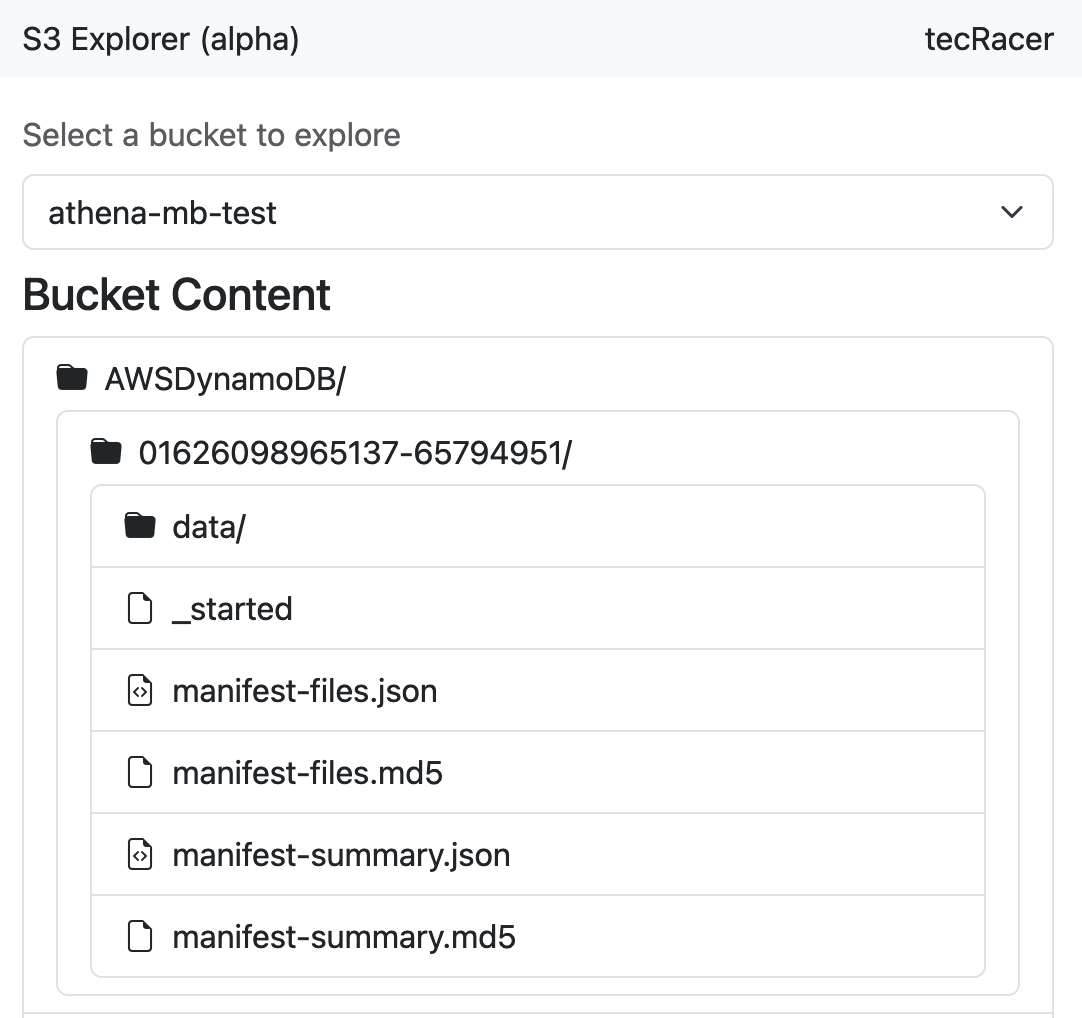

Since we can’t expect all data to be stored at the top of our virtual directory tree, we need a way to navigate into folders. The basis for this is hidden in the render_directory_list_item mentioned in the code snipped above.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

def render_directory_list_item(s3_path: str) -> dbc.ListGroupItem:

_, object_key = _s3_path_to_bucket_and_key(s3_path)

label = (

object_key.removesuffix("/").split("/")[-1] + "/"

if object_key.endswith("/")

else object_key.split("/")[-1]

)

output = dbc.ListGroupItem(

children=[

html.Span(

id={

"type": "s3-item",

"index": s3_path,

},

style={"cursor": "pointer", "width": "100%", "display": "block"},

children=[render_icon(s3_path), label],

n_clicks=0,

),

html.Div(

id={

"type": "s3-item-content",

"index": s3_path,

},

),

],

)

return output

This function renders a ListGroupItem for the given S3 Path. It doesn’t matter if it’s a directory or object. The important thing is the id argument to the html.Span class. You can see a dictionary with two keys - the type s3-item and the current S3 path as the index attribute. You can find a similar id for the html.Div below, just with the type s3-item-content. In combination, we can use these two to have our app render directory trees of (almost) arbitrary depth using a pattern-matching callback.

# frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py

@callback(

Output({"type": "s3-item-content", "index": MATCH}, "children"),

Input({"type": "s3-item", "index": MATCH}, "n_clicks"),

State({"type": "s3-item", "index": MATCH}, "id"),

prevent_initial_call=True,

)

def handle_click_on_directory_item(n_clicks, current_level):

"""

Executed when someone clicks on a directory item - folder or object.

"""

is_open = n_clicks % 2 == 1

if not is_open:

return []

s3_path: str = current_level["index"]

return render_directory_listing(s3_path)

This callback is triggered when the n_clicks attribute on Items of type s3-item changes, i.e., when we click on our ListGroupItem / Span and reports the total number of clicks on that item so far. Additionally, we get the id attribute of the item that caused the callback to fire and write to the Div of type s3-item-content with the matching id.

In the function we can now determine if we need to display or hide the content of the directory based on the number of clicks it received. Odd click numbers open the directory and even click numbers close it. Then, we extract the S3 path that we’re at and call our trusty directory rendering function. Here’s what the result looks like.

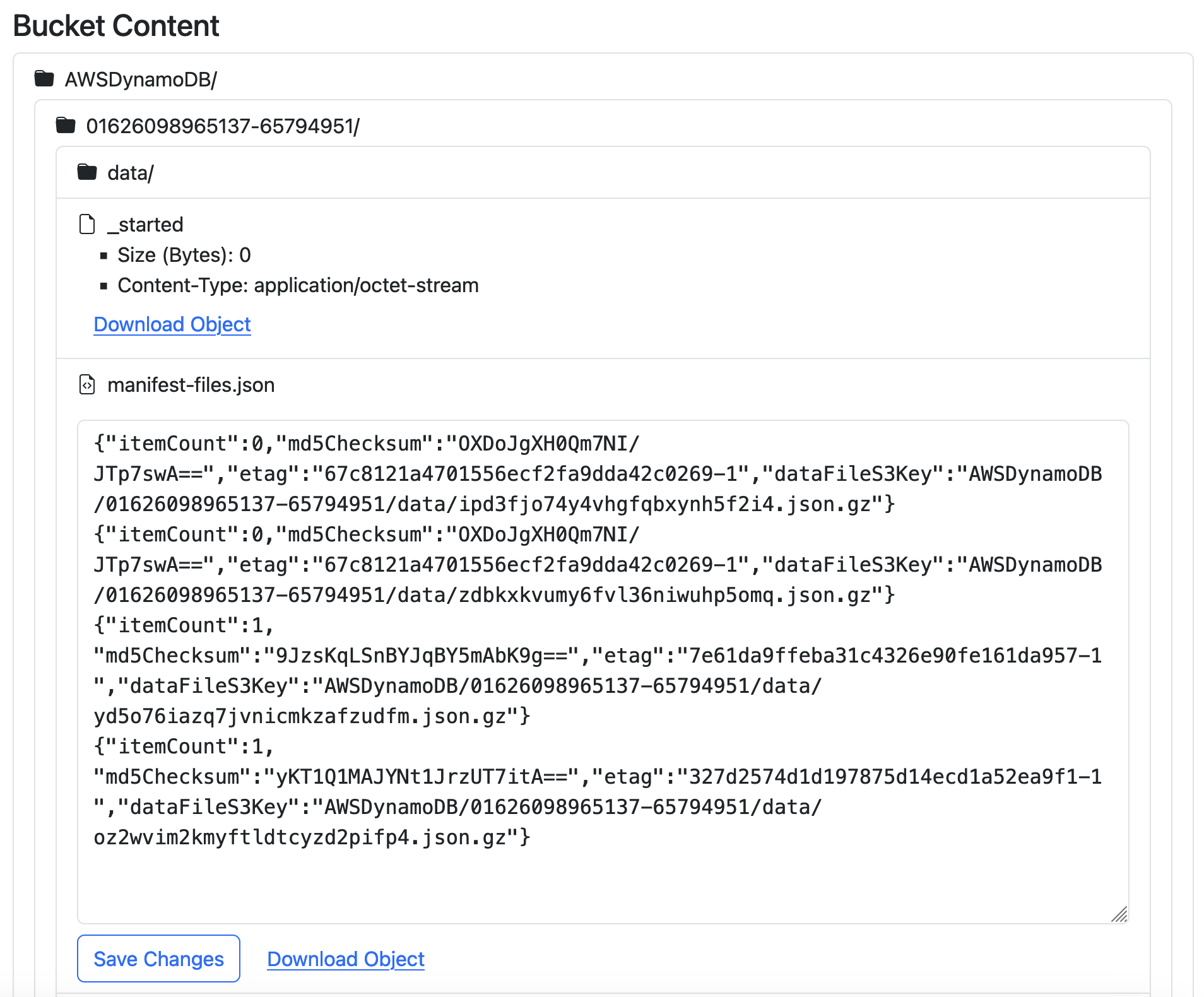

Since just displaying the directory tree wouldn’t be very useful, I also added some functionality to allow downloading objects via pre-signed URLs and even inline editing for some smaller text files.

Unfortunately, this post has already gotten quite long, and I need to talk a bit about security and limitations, so a detailed explanation of how that works will have to wait for another time - it relies on another pattern-matching callback implementation and some S3 API calls.

Deployment, Limitations & Security

You can deploy the solution to your own account, as explained in the Github repository. It’s basically a combination of sam build and sam deploy --guided because we need SAM to create an ECR repository for the docker image. After the deployment, you need to add credentials to the Parameter Store parameter; otherwise, you won’t be able to access the webapp. I didn’t include default credentials on purpose.

This solution is currently in alpha status, and it has several limitations; among others, it doesn’t do pagination on the list objects v2 API call, which means you’ll get at most 1000 objects per level. Arguably, anything more than that isn’t suitable for a UI anyway, and even 1000 is stretching it. You can choose which filetypes the inline editor is available for using the constants / global variables in frontend/pages/s3_explorer.py. Be aware that this approach doesn’t keep the original content type at the moment. Error/exception handling is also not very pretty at the moment - most missing permissions just result in CloudWatch logs being written and nothing happening on the frontend.

Whenever we expose information from our AWS accounts to other tools, security is a major concern. Here, all connections are TLS encrypted, and only authenticated requests are passed to the backend. You should be aware that the function has fairly broad S3 read/write permissions at the moment. I strongly recommend you limit those to the buckets that you actually need to be explorable from a webapp. I chose to not include any KMS permissions for the Lambda. If your S3 buckets are encrypted with KMS keys, you’ll have to add the kms:Decrypt permission for read access and kms:Encrypt + kms:GenerateDataKey for editing files.

Closing words

I hope this webapp illustrates how you can use the Serverless Dash stack to build powerful apps on AWS. Check out the code, stay tuned for further articles in this series, and get in touch if you want us to implement something similar for you.

— Maurice

Other articles in this series:

- Deploying a Serverless Dash App with AWS SAM and Lambda

- Adding Basic Authentication to the Serverless Dash App

- Build a Serverless S3 Explorer with Dash