Understanding Iterations in Ray RLlib

Recently I’ve been engaged in my first reinforcement learning project using Ray’s RLlib and Sagemaker. I had dabbled in machine learning before, but one of the nice things about this project is that it allows me to dive deep into something unfamiliar. Naturally, that results in some mistakes being made. Today I want to share a bit about my experience in trying to improve the iteration time for the IMPALA algorithm in Ray’s RLlib.

In case you’re not super familiar with the subject, let me very briefly explain the idea behind this approach. In Reinforcement Learning we try to teach a model how to behave in an environment. We do that by giving the model some information about the environment (observation), allowing it to perform actions, and rewarding it for these. We’re going to skip the difficult (and fun) part of defining the environment, observation, actions, and reward functions as they’re not that relevant to today’s story.

Instead, we’ll focus on the training process. The trainer (RLlib/Ray Tune) will try to train a model that maximizes the reward over a series of so-called steps in the environment. It will interact with the environment through actions and collect samples in the form of observation-action-reward-next-observation-tuples. It then uses an algorithm, in my case IMPALA (which I’m going to call Impala from now on because the other spelling is very shouty), to train a neural network in the hopes that it will learn to predict the optimal action to maximize the long-term reward based on an observation.

This trainer works in so-called iterations and reports statistical information at the end of an iteration. When we start a training we basically tell it: go ahead and train for x iterations or until y hours have passed, whichever comes first. I spent some time optimizing our environment in the hopes of decreasing how long it takes until I could see meaningful results from the trainings. I managed to speed some parts up significantly, but when I looked at the time it took to complete a single iteration, I seemed to be hitting a wall around 10.5 seconds.

At this point, you need to know that Ray collects a lot of metrics from a lot of components in the pipeline and to be frank, I understand only a small portion of them because there are literally dozens of them (and it feels like hundreds). There are also many dozens of knobs to turn in order to tweak how your model is set up and trained, and I’m getting better at understanding them, but sometimes it feels as if new Ray releases with more knobs come out faster than I can learn them. In fact, there’s always a low-level anxiety that you’re missing out on big improvements because you’ve chosen the wrong parameters. But that’s enough venting for now. Suffice it to say it’s a complex tool.

There I was trying to decrease the iteration times when I took a closer look at one of the trained models. Ray pickles the policy (Ray-lingo for model), allowing you to simply load it into memory and poke around in it with a debugger. Among the many configuration options that were set, I found a suspicious value called min_time_s_per_iteration with a default value of 10. You can imagine me sitting there after working at this for several hours, just facepalming. Initially, I tried to just set this value to 0 and run a training and suddenly the iterations were blazing fast, taking less than half a second to complete. Suspiciously fast. When something looks too good to be true, it probably is.

I dug deeper and then discovered that I had misunderstood what an Iteration actually is. I was operating based on the assumption that an iteration is very similar to an epoch in supervised learning, which means one pass over the training dataset. Turns out it’s not because of course it isn’t. In Reinforcement Learning, we don’t really have a static and limited training dataset. The model learns by interacting with the environment and gathering data (yes, it’s limited in other ways).

Let me share what my current understanding of an iteration in Ray’s RLlib is. An iteration is used by Ray to pause and take stock of the training progress. Think of it like the system taking a deep breath and doing a retrospective to figure out how far it has come. (With fewer post-its and awkward check-in questions.) In Ray, there are, to my knowledge, three main knobs to control how long an iteration is:

min_time_s_per_iterationmin_sample_timesteps_per_iterationmin_train_timesteps_per_iteration

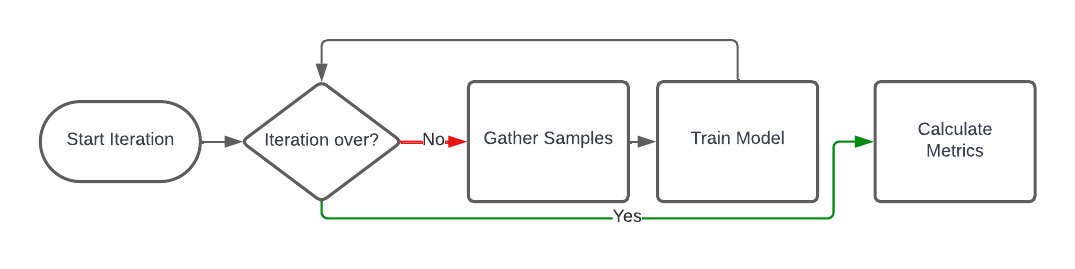

An iteration contains two steps that happen in a loop: gathering samples and training the model. Depending on the algorithm, these can be parallelized and may run asynchronously (e.g. in Impala). Gathering samples means that Ray uses the current version of the model to interact with the environment to gather new observations and rewards. It does this until it has enough samples for a training batch (configurable via train_batch_size). Next, it will use this training batch to train the model and then start collecting more samples based on the updated model.

The three parameters I mentioned control when this loop is terminated. If min_time_s_per_iteration is activated, it will spend at least that amount of seconds in this loop. If min_sample_timesteps_per_iteration is activated it will stop the iteration when that amount of samples have been generated. Last, min_train_timesteps_per_iteration stops the iteration once the model has been trained with that amount of samples. The meaning of timestep is defined by the count_steps_by configuration. At least one of them should be configured - otherwise, you get blazing-fast iterations with little work being done (check out the implementation for more details).

You may wonder why there are different metrics for sample and train timesteps. That’s because sample generation and training may be parallelized (e.g. in Impala), and depending on where the bottleneck is, one may be reached earlier than the other.

The next step after understanding this behavior was to select a sensible configuration. In our case, the default of 10 seconds didn’t make a lot of sense because an arbitrary time period doesn’t tell us much about the environment’s or the model’s performance. We’re constrained by the amount of historical data we have available and thus the number of meaningfully different experiences we can offer to the same model. That’s why we chose a value that roughly matches the number of different experiences. In a way, that means my original mental model of the epoch applies again, more or less, because this number approximates our training dataset. Your choice should depend on the problem you’re trying to solve.

In summary: Ray is a complex and powerful framework that allows you to configure all kinds of things. It can be overwhelming, and I’m looking forward to the next time that will make me feel like screaming at my computer. Oh, and check your assumptions. Mental models for machine learning may not work for all aspects of machine learning, but I should have known that one.

— Maurice

Title image by Oudom Pravat auf Unsplash