The beating heart of SQS - of Heartbeats and Watchdogs

Using SQS as a queue to buffer tasks is probably the most common use case for the service. Things can get tricky if these tasks have a wide range of processing durations. Today, I will show you how to implement an SQS consumer that utilizes heartbeats to dynamically extend the visibility timeout to accommodate different processing durations.

The simple queue service is one of the oldest AWS services, so chances are you’re familiar with it. It’s one of the few services where the simple in the name is still accurate. SQS provides a message queue that implements the producer/consumer pattern. One or more producers add messages to the queue, and asynchronously one or more consumers read those messages and process them somehow. Messages are processed at least once, which means a consumer usually has exclusive access to a message, but that’s not guaranteed.

While the consumer works on a message, it is hidden from other consumers for a period called the visibility timeout. This visibility timeout has an upper limit of 12 hours, but you can set it to whatever value you want between a few seconds and 12 hours. After the visibility timeout expires, the message becomes available to other consumers for processing. This is a convenient way to handle processing failures where a consumer fails to process a message. After the timeout expires, another can pick up where the former left off and try again.

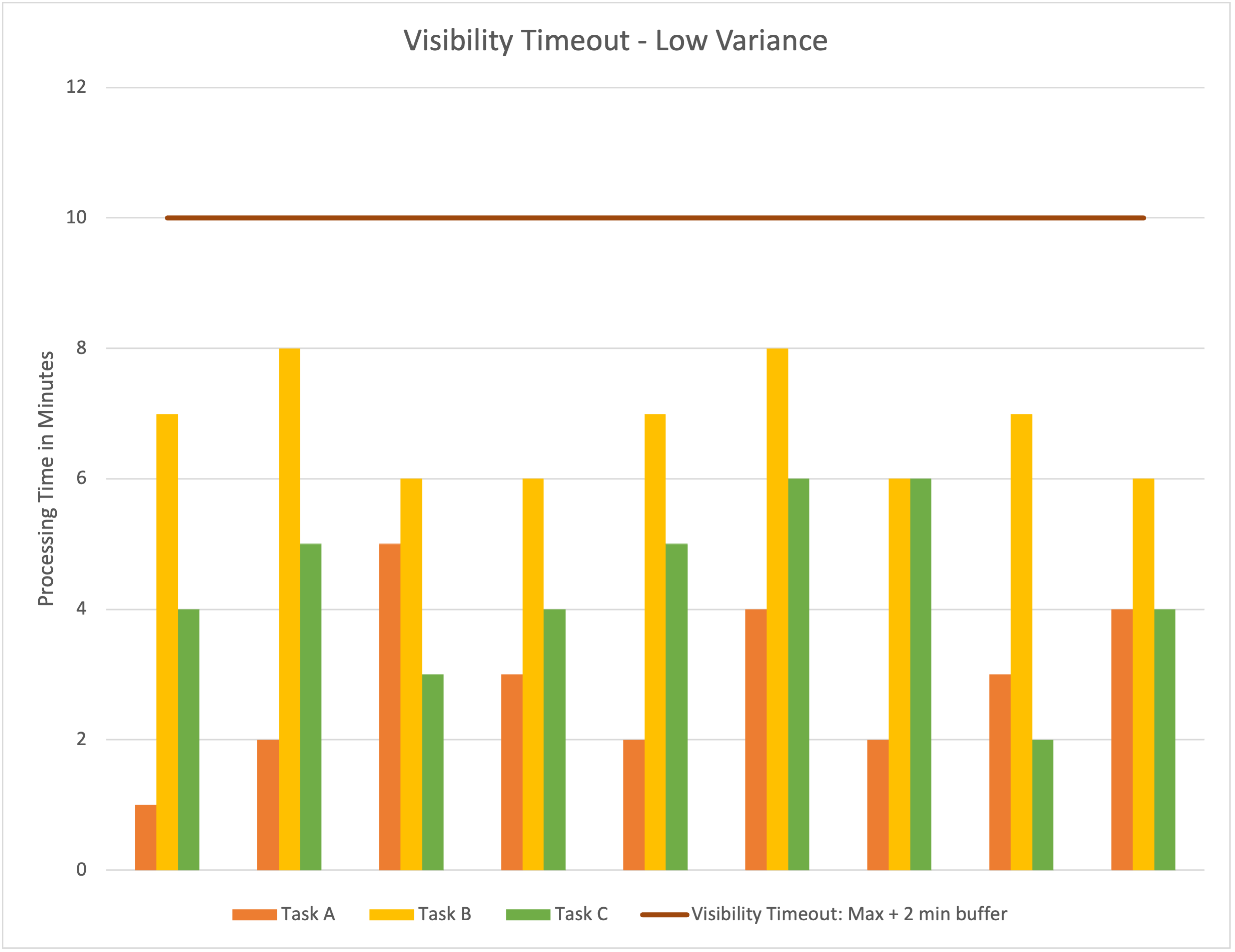

A task or job queue is one of the most common use cases for SQS. Producers add tasks to a queue, and a group of consumers works on those tasks asynchronously. Using an identical visibility timeout for all messages works well if the tasks are uniform in complexity and the time it takes to complete them. With the knowledge that processing a message takes no more than 10 minutes, you can confidently use 10 minutes as the visibility timeout when you perform the ReceiveMessage API call to fetch messages.

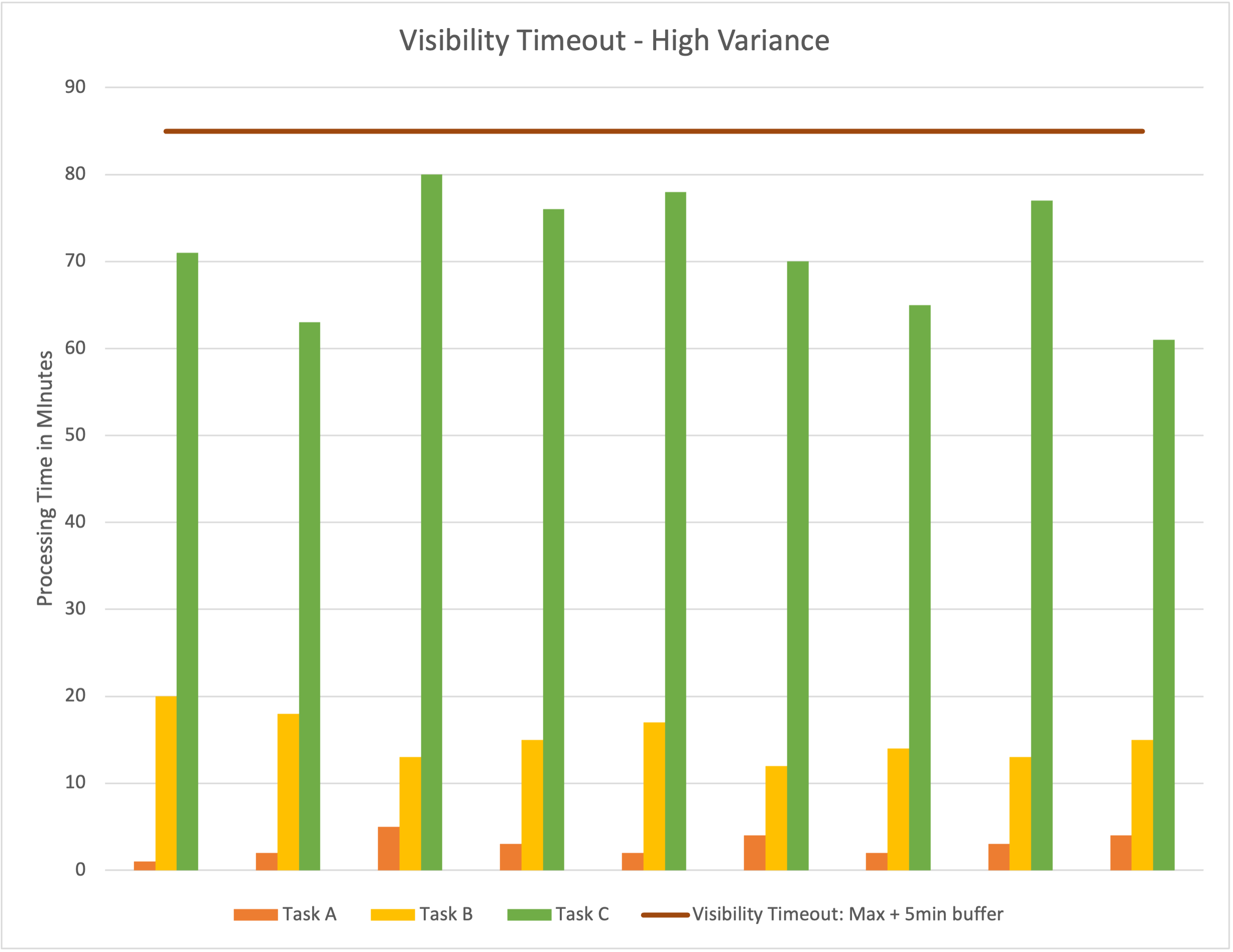

A lot of variance in processing duration makes this troublesome. Some of your jobs may be completed in 30 seconds, and others may take more than an hour or multiple hours. What do you pick as the visibility timeout? Since you don’t know ahead of time what messages the queue will return to you, you can’t do it dynamically based on the task you receive. The naive approach would be to select the maximum duration it takes to process a message, as we did in the first example.

There are trade-offs, though. Suppose processing for a 30-second message fails. The message will become available to the next consumer at the end of the visibility timeout. Here it would take around 85 minutes to retry processing the message. If someone is waiting for that task, this is less than ideal. Another scenario would be us not having access to historical data, so we can’t make an educated guess about a good value for the visibility timeout. How can we improve this situation?

SQS allows us to change the visibility timeout for a message after we have received it using the ChangeMessageVisibility API call. We can combine this with the ideas of a Watchdog process and heartbeats to create a more adaptive approach that reduces the time until failed tasks are retried. Let’s explore these concepts.

Most non-AI entities reading this should be familiar with heartbeats. They are a pretty good indication that you’re still alive. In IT, a heartbeat is a kind of signal that we periodically send to indicate we’re still alive and kicking. In the context of SQS, we can extend the visibility timeout of our messages every few minutes if we know that processing is still in progress. If we fail to extend the visibility timeout, that indicates the process is dead, and after a short period, the message becomes available for reprocessing by another consumer.

Watchdogs should also be familiar from the non-digital world. They monitor an area and alert if something is happening. Sometimes they take more active or, shall we say, bitey roles in responding to perceived activities. We can use the idea of a watchdog as well. We’ll have a process that monitors if the task is still being worked on and sends periodic heartbeats to SQS to indicate that’s the case.

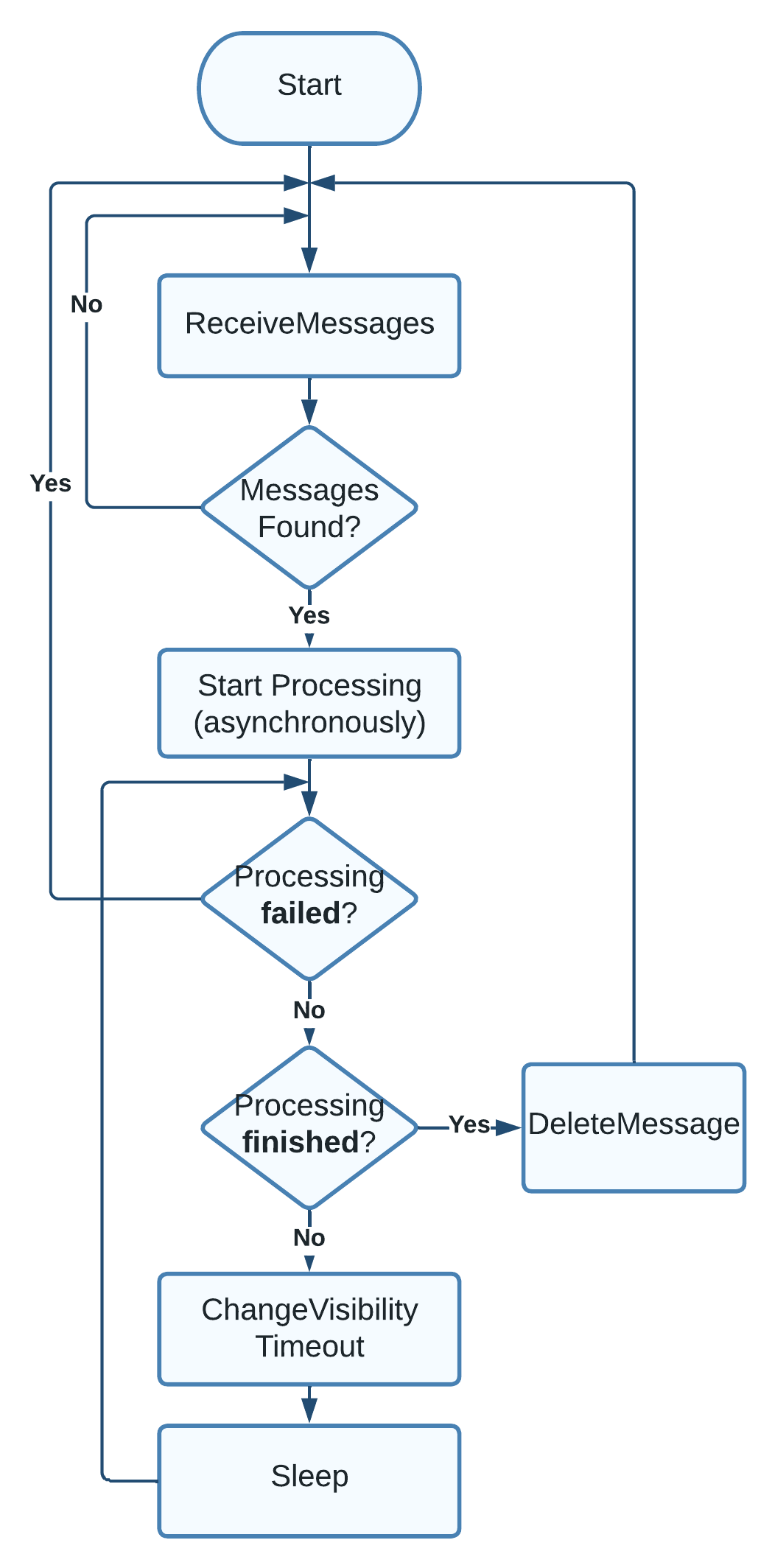

Combining these ideas allows us to design the logic a process needs to implement to achieve this adaptive behavior. I will use the flowchart below to illustrate what’s going on. There’s an inner and an outer loop. The outer loop waits for more messages, and the inner loop processes individual messages. For each new message, the inner loop starts an asynchronous process that works on the message. This can be a separate thread or process that performs the work that the message asks for. It’s vital that this is not in the same thread as our watchdog. Otherwise, this won’t work.

After processing starts, the inner loop begins. It terminates if processing fails, so the outer loop can receive a new message. As long as the work is in progress and has not failed, we periodically extend the visibility timeout until work is completed and delete the message from the queue. If anything goes wrong, e.g., the instance dies, the message will be available to another consumer relatively quickly.

Pictures are cheap. Let’s look at some code that you can also find on GitHub. You need the AWS SDK for Python and a standard SQS queue to run this yourself. We begin with code that can send a few dummy messages to our SQS queue.

def create_tasks_in_queue(queue_url, number_of_tasks_to_create) -> None:

"""

Sends number_of_tasks_to_create to the queue.

"""

sqs_res = boto3.resource("sqs")

queue = sqs_res.Queue(queue_url)

number_of_tasks_to_create = 3

queue.send_messages(

Entries=[

{"Id": str(n), "MessageBody": f"Task #{n}"}

for n in range(number_of_tasks_to_create)

]

)

LOGGER.info(

"📮 Sent %s messages to the queue '%s'", number_of_tasks_to_create, QUEUE_NAME

)

The outer loop is implemented in the main function. First, we add the tasks to the queue and then try to read the messages. Instead of the infinite loop from the flowchart, we’re running until we have successfully processed the same number of messages we sent to the queue.

def main():

#...

queue_url = boto3.client("sqs").get_queue_url(QueueName=QUEUE_NAME)["QueueUrl"]

LOGGER.debug("Queue-URL: %s", queue_url)

number_of_tasks_to_create = 3

create_tasks_in_queue(queue_url, number_of_tasks_to_create)

sqs_res = boto3.resource("sqs")

queue = sqs_res.Queue(queue_url)

messages_successfully_processed = 0

while messages_successfully_processed < number_of_tasks_to_create:

messages = queue.receive_messages(

MaxNumberOfMessages=1,

VisibilityTimeout=5,

WaitTimeSeconds=5,

)

if messages:

message = messages[0]

LOGGER.info("📋 Got message '%s' from the queue", message.body)

start_processing(message)

result = monitor_processing_progress(message, visibility_timeout=5)

messages_successfully_processed = (

messages_successfully_processed + 1

if result

else messages_successfully_processed

)

else:

LOGGER.info("Found no new messages...")

The watchdog & heartbeat logic is in the monitor_processing_progress function. I implemented the function recursively instead of a loop - mostly because I can. A loop would be okay here as well. You can clearly see the two decisions of the inner loop here where processing_failed() and processing_completed() are called to check the processing state. If you were to use this code, these are the functions you’d need to implement yourself.

def monitor_processing_progress(sqs_message, visibility_timeout: int) -> bool:

"""

Check if the message is still being processed or processing failed.

Provide the heartbeat to SQS if it's still processing.

"""

if processing_failed():

LOGGER.info("💔 Processing of %s failed, retrying later.", sqs_message.body)

return False

if processing_completed():

LOGGER.info("✅ Processing of %s complete!", sqs_message.body)

sqs_message.delete()

return True

LOGGER.info("💓 Processing of %s still in progress", sqs_message.body)

visibility_timeout += 5

sqs_message.change_visibility(VisibilityTimeout=visibility_timeout)

time.sleep(5)

return monitor_processing_progress(sqs_message, visibility_timeout)

Right now, these functions are placeholders that return a failed state 20% of the time and the completion complete 50% of the time. This is just so the demo is more interesting.

def is_successful(chance_in_percent: int) -> bool:

"""Returns true with a chance of chance_in_percent when called."""

return random.choice(range(1, 101)) <= chance_in_percent

def processing_failed() -> bool:

"""

This is where you'd determine if processing the message

failed somehow, this could mean checking logs for errors,

checking if a process is still running, ...

"""

percent_chance_of_failure = 20

return is_successful(percent_chance_of_failure)

def processing_completed() -> bool:

"""

This is where your watchdog would check if the processing

is completed, this may mean checking for files/ status entries

in a database or whatever you come up with.

"""

percent_chance_of_success = 50

return is_successful(percent_chance_of_success)

If we run the code, we may see an output like this:

📮 Sent 3 messages to the queue 'test-queue'

📋 Got message 'Task #0' from the queue

🎬 Starting to process 'Task #0'

💓 Processing of Task #0 still in progress

💓 Processing of Task #0 still in progress

✅ Processing of Task #0 complete!

📋 Got message 'Task #2' from the queue

🎬 Starting to process 'Task #2'

💔 Processing of Task #2 failed, retrying later.

📋 Got message 'Task #1' from the queue

🎬 Starting to process 'Task #1'

✅ Processing of Task #1 complete!

📋 Got message 'Task #2' from the queue

🎬 Starting to process 'Task #2'

✅ Processing of Task #2 complete!

We sent three messages to the queue, and it first worked on task 0, which took multiple seconds to complete, so two heartbeats were sent to extend the visibility timeout. Next, SQS returned task 2, which we failed to process, so it was returned to the queue. Afterward, task 1 is available and immediately processed successfully. Finally, Task 2 appears again and is successfully completed.

I’ve shown you how to implement an SQS consumer that dynamically updates the visibility timeout to accommodate different processing durations. You should be aware that this doesn’t change the maximum limit. It can only extend the processing until 12 hours are reached, then SQS will respond with an error. While this is a reasonably adaptive approach, it also adds a bit of complexity to your consumer. If your processing durations are very stable and you don’t have low latency targets, it’s probably best to stick to a more straightforward implementation.

Thank you so much for reading. Hopefully, you learned something useful. Feel free to check out the code on GitHub if you want to dive deeper.

— Maurice

Title Photo by Jair Lázaro on Unsplash