Understanding Apache Airflow on AWS

Apache Airflow doesn’t only have a cool name; it’s also a powerful workflow orchestration tool that you can use as Managed Workflows for Apache Airflow (MWAA) on AWS. This post will explain which problems the service solves, how you can get started, and the most important concepts you need to understand. In the end, we’ll bring everything together with an example use case.

The Apache ecosystem is full of projects, and often, the project’s name doesn’t indicate what the tool does (think Pig, Cassandra, Hive, etc.). Airflow is another example of that. Meaning you won’t have a clear idea in your head of what the service does when you first come upon the name. If you think similar to us, you’ll first ignore these projects until the name keeps popping up, and then you begin investigating what all the buzz is about. Airflow kept showing up on our radar, and when the first projects came around, we dove deep into it. We can report that the tool is pretty cool, and that’s why we want to give you some insight into it.

If you’re familiar with the AWS ecosystem, you can think of Airflow as a mix of step functions and Glue workflows. Its main task is to orchestrate ETL processes. Acronyms are annoying, but we’ll continue using ETL here. It refers to Extract-Transform-Load and describes preparing data for analysis by manipulating or enriching it somehow. Standard tools are Glue, Spark, Elastic Map Reduce (EMR), Lambda, or Athena. ETL processes tend to increase in complexity over time, and you’ll find that you need to schedule and orchestrate different services in conjunction with each other to process your data. Here is where Airflow can help.

Airflow is a popular open-source tool that allows you to describe your ETL workflows as Python code and makes it possible to schedule and visually monitor these workflows while at the same time providing broad integrations in the AWS ecosystem and with 3rd party tools. Additionally, it provides a single interface to watch all your ETL processes, which people in operations roles will value.

In AWS, MWAA or Managed Workflows for Apache Airflow provides a managed Airflow Environment. While not a memorable name, it is descriptive and a well-built service. You need to have a VPC with at least two private subnets to start using the service. The VPC has to be owned by the account. Additionally, we need to create a role that our Environment can use to trigger other services. This Environment will be responsible for hosting our ETL workflows. The role requires access to all the services you intend to use in the workflows, which means it will have fairly broad permissions. It’s not great from a security perspective, but there isn’t too much we can do about this for now. Strategies to improve the situation may be the topic for a future blog post - let us know if you’re interested.

Once you have the VPC and the role, you can create your Environment, which is highly available by default. You have to specify an S3 path where your workflow definitions (DAGs, more on that later) will be stored. The role the Environment can use is another mandatory configuration. You can optionally set paths in S3 to a requirements.txt that specifies which additional Python packages to install and a path to a Plugins.zip, also in S3 that can contain other dependencies. It’s also good to increase the log level here to get more insights into what’s going on in the Environment.

Now you’ll need patience while the Environment is created because it can take between 25 and 30 minutes, and if you later update it, that may take around 15 minutes. You’ll want to avoid messing this up too many times. Waiting for Environments to spin up or reconfigure is not a fun experience. Once it is in the ready state, we have a fancy Environment that allows us to log in. Right now, this doesn’t do anything besides increase our AWS bill. Let’s change that by adding our workflows. To do that, we have to cover a bit of theory.

Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) describe workflows in Airflow, which is a fancy way of saying that a workflow can’t have loops. A DAG is written in Python and stored in an S3 bucket at the location we configured when setting up the Environment. MWAA periodically fetches all the DAGs from that path and adds them to the Environment - it can take a minute until changes show up. However, this is usually a matter of seconds.

DAGs begin with a bit of setup code that defines when and how they’re executed. Then there is a set of tasks that make up the workflow. Tasks come in two varieties: Sensors and Operators:

- Sensors block execution of the DAG until a particular condition is fulfilled. It can, for example, wait until an external Endpoint returns a specific status code or a file appears in some location. You can think of this as the

awaitpart in anasync ... awaitpattern, which you may be familiar with from asynchronous processes. - Operators are at the heart of DAGs. They trigger external services and manage their execution. You can use one of the many pre-built operators, for example, to run a Query in Athena or create your own based on shell scripts or Python code.

Each task uses a connection to talk to a service. Connections consist of a type and a set of credentials that define how to connect to a service. Operators and Sensors often use a default connection such as aws_default when not configured otherwise. In this example, aws_default uses the role we configured when setting up the Environment. MWAA Environments already have a lot of connections in place when you spin up the Environment.

After defining the tasks, it’s essential to define their execution order. You can use this to establish dependencies between them and run them in parallel if possible. You can use the bitshift operators (>>) in Python to chain your tasks, which is a neat way of doing that. Next, we will look at an example of a simple DAG.

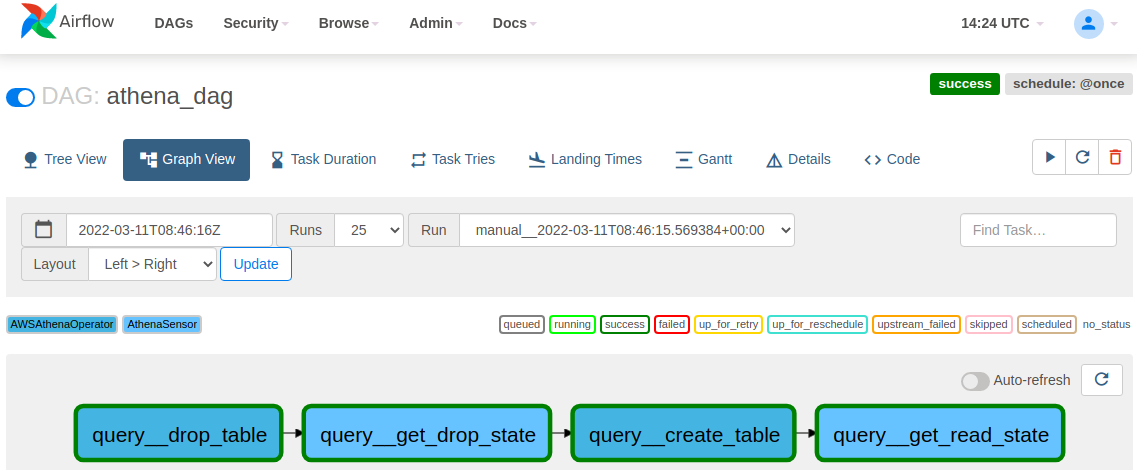

Below you can see the definition of a simple DAG that interacts with Athena. It first executes a query to delete a table if it exists and then waits for that query to finish using a sensor. Next, it executes another query to create a new table and then waits for that to complete. We also define when this DAG is scheduled. In this case, we only run it once manually.

# The DAG object; we'll need this to instantiate a DAG

from airflow import DAG

# Athena Operators and Sensors, come preinstalled in MWAA

from airflow.providers.amazon.aws.operators.athena import AWSAthenaOperator

from airflow.providers.amazon.aws.sensors.athena import AthenaSensor

from airflow.utils.dates import days_ago

from datetime import timedelta

import os

# Naming the DAG the same as the filename

DAG_ID = os.path.basename(__file__).replace(".py", "")

# AWS variables

S3_OUTPUT_BUCKET = "my-athena-bucket"

ATHENA_TABLE_NAME = "athena_example"

ATHENA_DATABASE = 'default'

# These args will get passed on to each operator

# You can override them on a per-task basis during operator initialization

DEFAULT_ARGS = {

'owner': 'airflow',

'depends_on_past': False,

'email': ['airflow@example.com'],

'email_on_failure': False,

'email_on_retry': False,

}

# Some Athena SQL Statements, ideally shouldn't be here

QUERY_DROP_TABLE = f'DROP TABLE IF EXISTS {ATHENA_TABLE_NAME};'

QUERY_CREATE_TABLE = """

CREATE EXTERNAL TABLE IF NOT EXISTS athena_example (

.../* Long statement here */

"""

with DAG(

dag_id=DAG_ID,

default_args=DEFAULT_ARGS,

dagrun_timeout=timedelta(hours=2),

start_date=days_ago(1),

schedule_interval='@once',

tags=['athena'],

) as dag:

drop_table = AWSAthenaOperator(

task_id='query__drop_table',

query=QUERY_DROP_TABLE,

database=ATHENA_DATABASE,

output_location=f's3://{S3_OUTPUT_BUCKET}/',

sleep_time=30,

max_tries=None,

)

get_drop_state = AthenaSensor(

task_id='query__get_drop_state',

query_execution_id=drop_table.output,

max_retries=None,

sleep_time=10,

)

create_table = AWSAthenaOperator(

task_id='query__create_table',

query=QUERY_CREATE_TABLE,

database=ATHENA_DATABASE,

output_location=f's3://{S3_OUTPUT_BUCKET}/',

sleep_time=30,

max_tries=None,

)

get_create_state = AthenaSensor(

task_id='query__get_read_state',

query_execution_id=create_table.output,

max_retries=None,

sleep_time=10,

)

drop_table >> get_drop_state >> create_table >> get_create_state

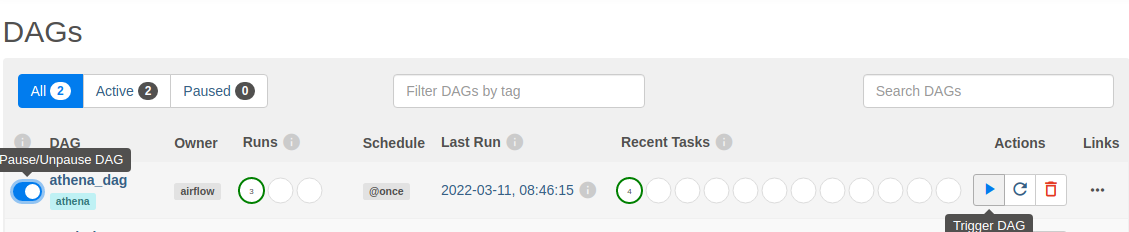

Once we upload this DAG to the S3 path we configured earlier, the Environment picks it up, becoming visible in the Airflow interface. Next, we need to enable it, and then we can see a successful execution.

Here, you’ve seen a few examples of an operator interacting with AWS services. That’s only one of many available operators and sensors for AWS, which you can read more about here. AWS also provides a Github repository full of example use cases in the form of DAGs, which is available here. This should be a good starting point to dive deeper into Airflow and its use cases if you want to learn more about Airflow concepts the documentation is here to help you.

Before we summarize, let’s maybe talk about when not to use Airflow. If all you need to do is orchestrate fewer than ten workflows that run entirely in AWS, Airflow may be an expensive solution. Running an Airflow Environment starts at around $35-40 per month, and that’s the smallest version. You can run many step functions for that kind of money, but you will have to build them as well, and depending on complexity, the math may work out differently. Airflow has a lot going for it, though, especially if you need to work with 3rd party providers because there are many pre-built solutions.

Summary

We covered which problems Apache Airflow can solve and how to create your Airflow Environment using MWAA in AWS. We also explained the basics of DAGs and the associated components and gave you a simple DAG example.

Hopefully, you learned something from this post, and we’re looking forward to your questions, feedback, and concerns. Feel free to reach out to us through the profiles listed in our Bios.

— Peter & Maurice