How the Application Load Balancer works

Load Balancers are a vital component in scalable and fault-tolerant architectures. The basic idea is relatively simple: a central element distributes incoming requests to different backend nodes. The implementation involves a fair bit of complexity, however. This post will explain the various components, how they interact, and how requests flow through a load-balanced architecture.

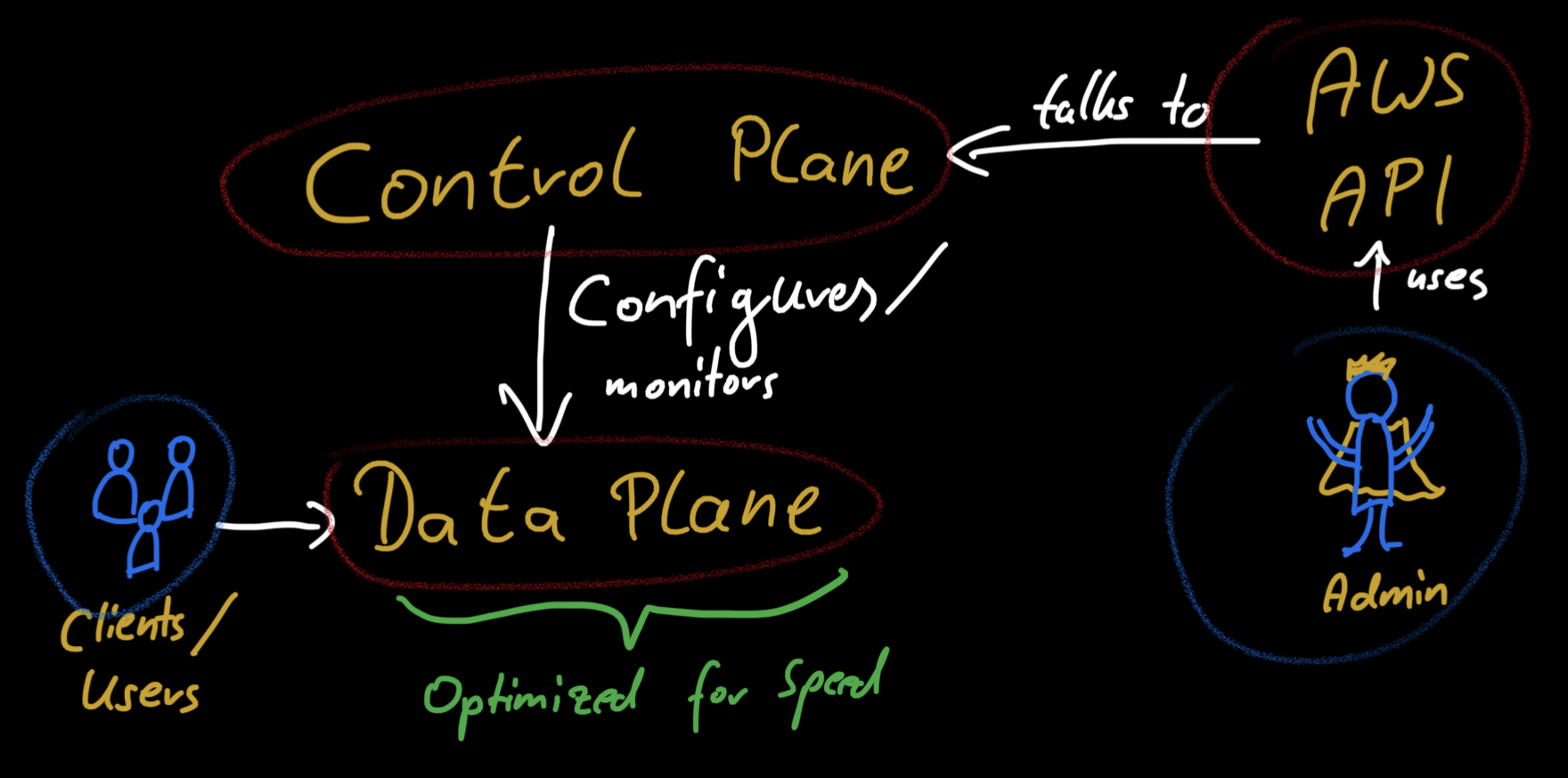

The simple mental model of one component that acts as the single point of entry and distributes traffic to your backend is good enough for most architecture discussions. If you‘re implementing this, you‘ll face many more components: load balancers, listeners, rules, target groups, security groups, and DNS records. Some of these are only logical components on the control plane that set up and configure the underlying physical infrastructure of the data plane. It makes sense to look at this architecture on these two levels.

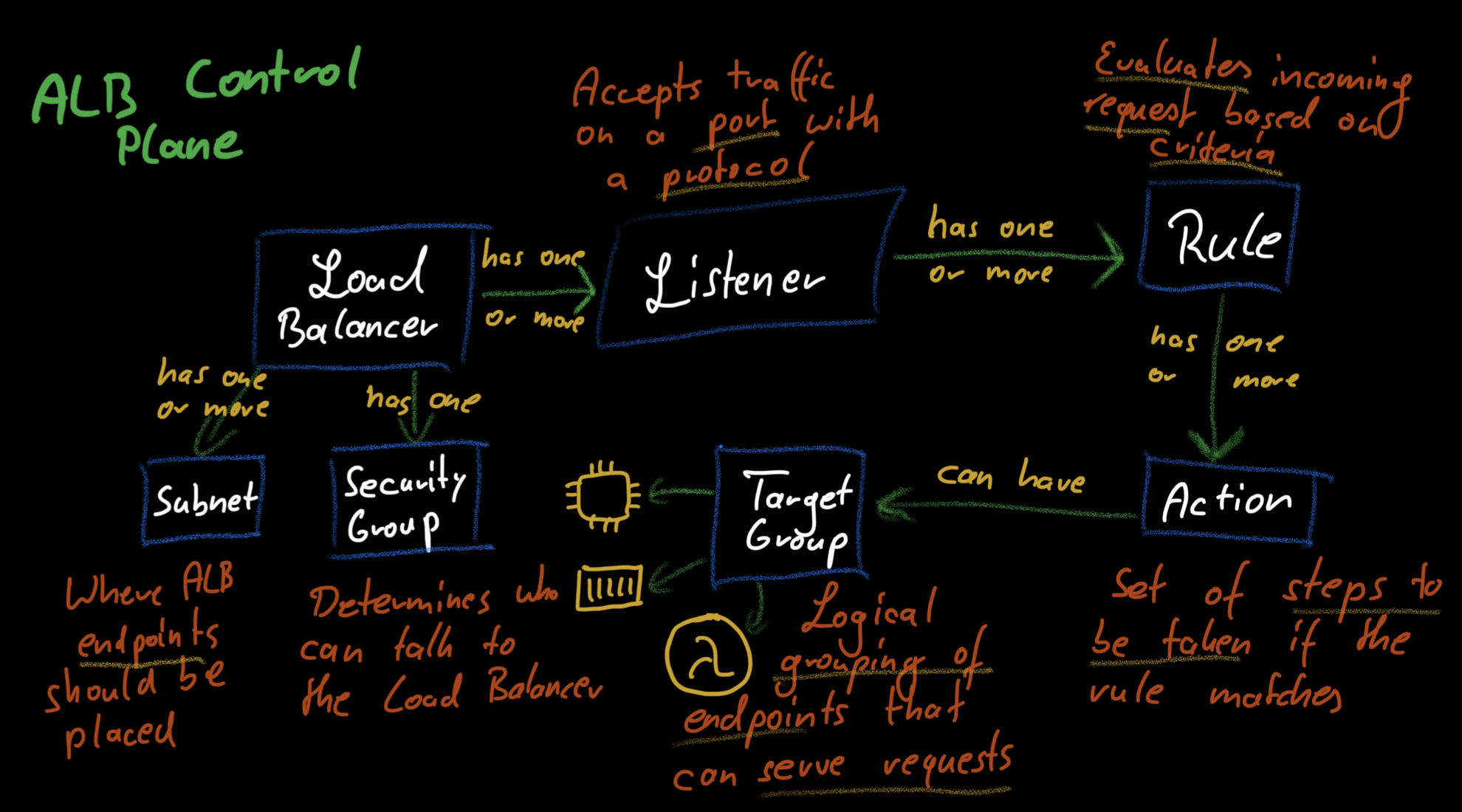

We‘ll start with the control plane. If we think back to our mental model, the load balancer is our application’s central point of contact. That means that you need to tell your customers that a load balancer is responsible for your app. DNS solves this problem. Each load balancer has a DNS name that we can use to talk to it. All we need to do is to set up an ALIAS or CNAME record for our domain and point it to the load balancer‘s DNS name. ALIAS records are specific to AWS, and we can think of them as providing a more efficient alternative to CNAME records.

Now we have set up a way for our users to find the load balancer. Next, we have to decide on the protocols the load balancer will support. Application Load Balancers support HTTP and HTTPS connections (and gRPC, but if you‘re using that, you‘re most likely not in the target audience of this article). ALBs have the concepts of listeners to enable a protocol. Each listener can support a single protocol, so you need two listeners to have both HTTP and HTTPS. HTTPS listeners are a bit more complex because you need to configure a certificate for them to use to enable encrypted connections with the client. The listeners are each associated with a port that allows the clients to connect.

After creating the listeners, we‘re now in a position where the clients know how to find our app and connect to the load balancer through HTTP/HTTPS. Now we have to decide what to do with that traffic. Here is where listener rules come in. A set of rules defines how each listener handles traffic. Rules can check for specific conditions and are evaluated from top to bottom. There is also a default rule that matches if no other rule applies.

Each rule can have one or more actions that define what‘s supposed to happen with traffic if the rule matches. These actions can include sending back a static response, invoking a Lambda function, authenticating clients, or forwarding the traffic to the backend. Here is where it gets interesting. We need a way for the load balancer to learn about the available backends. Target groups are what enable this. A target group contains a set of endpoints that can handle traffic in the backend. These can, for example, be containers or EC2 instances.

How are target groups populated? It depends. I know, it‘s frustrating. You can manually add endpoints to them or integrate AutoScaling, ECS Services, or EKS for the target groups to be filled with endpoints. Services like AutoScaling, ECS, or EKS automatically manage the entries in the target group. AutoScaling will, for example, make sure that newly launched EC2 instances are added to the group and terminated instances get deleted.

To complete the list of components on the control plane, we need to look at one more thing: networking. Each load balancer has a security group that determines who can access the load balancer. It also has a set of subnets from which it can receive traffic. Subnets are what bring us to the data plane. Next, we‘ll explore how these components interact to bring load balancers to life.

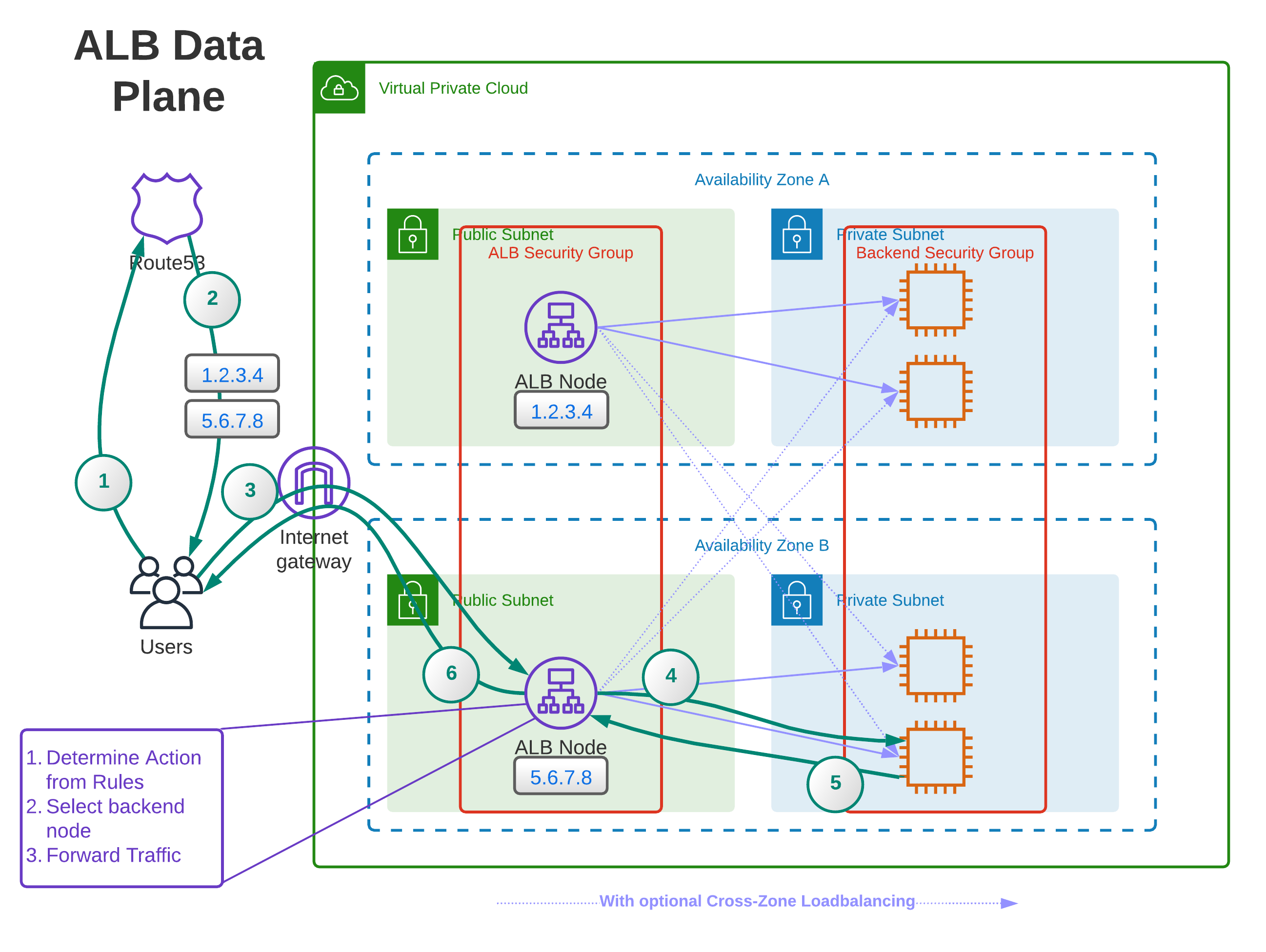

One thing that should make you suspicious about the mental model of load balancers outlined above is that it‘s one thing that‘s supposed to enable scalability and high availability for your application; one component. High availability and a single point of failure don‘t go well together. Here is where the mental model is inaccurate. A load balancer is not one component. On the data plane, multiple nodes accept traffic from clients.

These ALB nodes are distributed across the availability zones and subnets attached to the load balancer. They make high availability possible because they‘re not one thing. The interesting question is how the client works with that. Usually, we think of DNS as something that returns an IP address for a Hostname. That‘s true for the most part, but it can also respond with multiple IP addresses. When you do a DNS lookup for the DNS name of your ALB, you‘ll find that you‘ll get multiple IP addresses in the response. These are the IPs of (some of) the ALB-nodes.

The client can connect to each of these IP addresses, and there is no explicit standard on how to choose which one. Some randomize it, some pick the first one, some the last - it doesn‘t matter. The point is that they have a set of IPs to connect to, so they can choose another one if one of the IPs is unavailable in the rare event that an availability zone goes offline.

Now that the client has selected an IP address from the list, it can connect to the ALB node. Assuming the security groups allow the connection, the client can contact the ALB node. The node accepts traffic on the ports configured in the listeners on the control plane. It has a copy of all rules associated with those listeners (for performance reasons) and evaluates on the node what to do with requests. If the matching rule tells us to forward traffic to a target group, the load balancer picks an endpoint from the target group.

It‘s not clear whether the load balancer node caches information about the endpoints in the target group, but it would make sense. In any case, it selects a node from the target group and forwards the traffic to that node. Assuming the backend node‘s security group allows traffic from the ALB-security group, the backend can now work on the request and send the response to the load balancer, passing it on to the client.

I guess that most of the control plane information, such as listener rules and target groups, is cached on the ALB nodes because it‘s relatively static. Whether AWS pushes updates of these resources to the nodes or the nodes periodically pull them is an implementation detail that doesn’t concern us.

This has been an explanation of how the Application Load Balancer works. Hopefully, you find it useful. If there are any questions, feedback, or concerns, please reach out to me via the channels mentioned in my bio.

— Maurice