Simplify your code and save money with Lambda Event Filters

In this post I’m going to explore how the new event filters in AWS Lambda can be used to implement the data model for a video streaming website in DynamoDB. I’ll explain why this feature makes your code simpler and allows you to save money in the process.

At the end of 2021 AWS launched a new feature for Lambda functions: event filters for different kind of event sources. When you used an event source in the past, any event coming from it would trigger your code and you needed to figure out in your code if you wanted to act on it. This added some boilerplate code to your lambda functions and some cost to your AWS bill, because often your code would be invoked needlessly.

With the launch of event filters this changes for some data sources. AWS now allows you to filter events for SQS, Kinesis and DynamoDB before they hit your Lambda function. This allows you to offload this undifferentiated heavy lifting to AWS at no additional cost and at the same time simplify your own code, because you can throw out (big parts at least) of the existing filter code. Let’s see how this can be used.

Since I’m a big fan of DynamoDB I focused on a DynamoDB use case here. DynamoDB is not great at computing aggregates on the fly. That’s why we typically have aggregate items that hold statistical information and are updated asynchronously through a Lambda function whenever data changes in the table. An example for this are video statistics on a YouTube-like video-streaming website. This is what we’ll explore now.

Our video website wants to collect and share certain statistics about videos and users. Each video can be liked or disliked and viewed by users. We want to track the number of likes, dislikes, and views as well as the total viewing-duration per video. For each user we also want to keep track of how many videos the liked, disliked, and viewed as well as their total viewing duration. Synchronously managing these aggregates at scale is challenging at best.

That’s why we borrow a pattern from event sourcing: we write view and vote events to the table and asynchronously update these statistics in the background using streams.

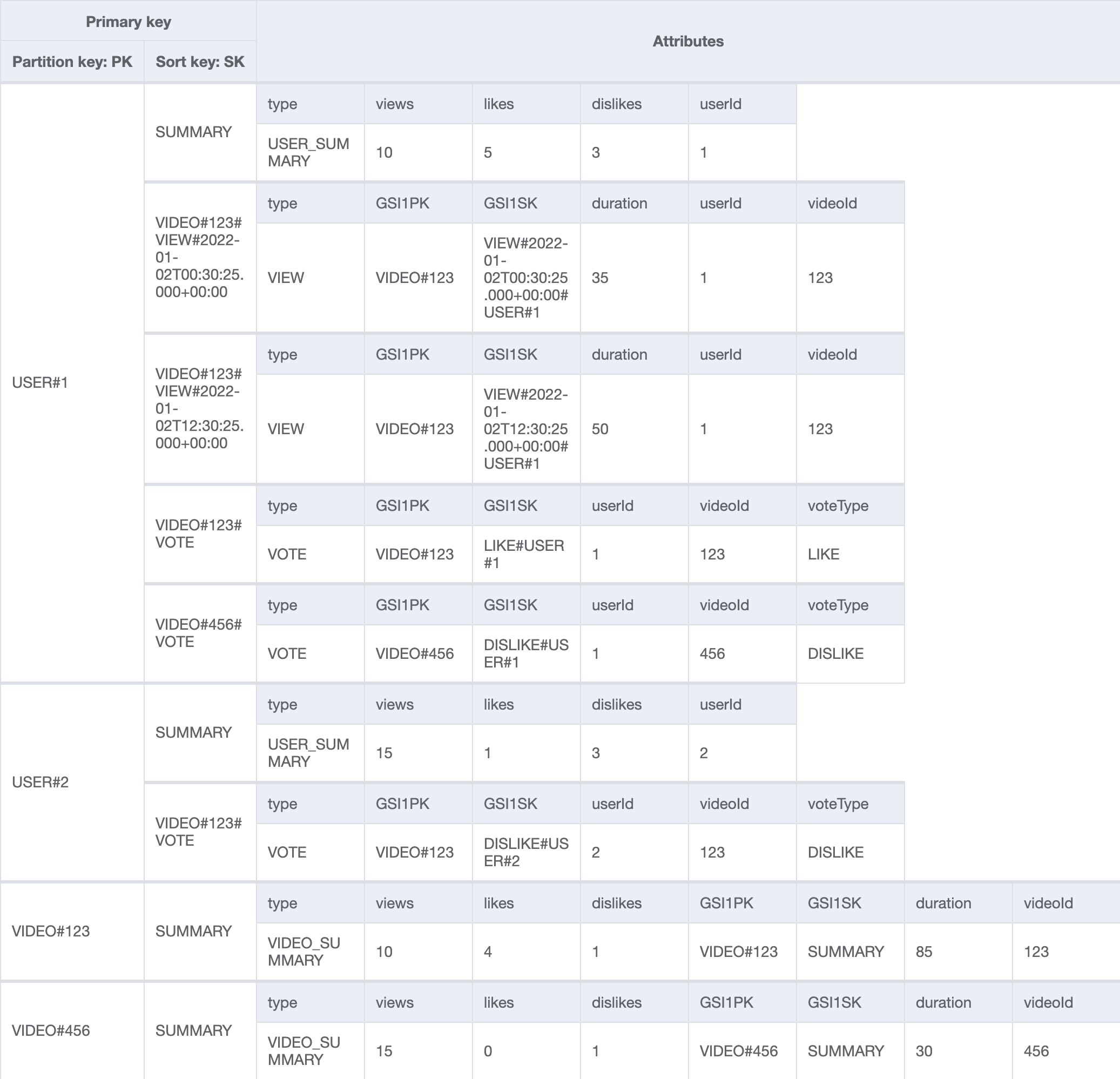

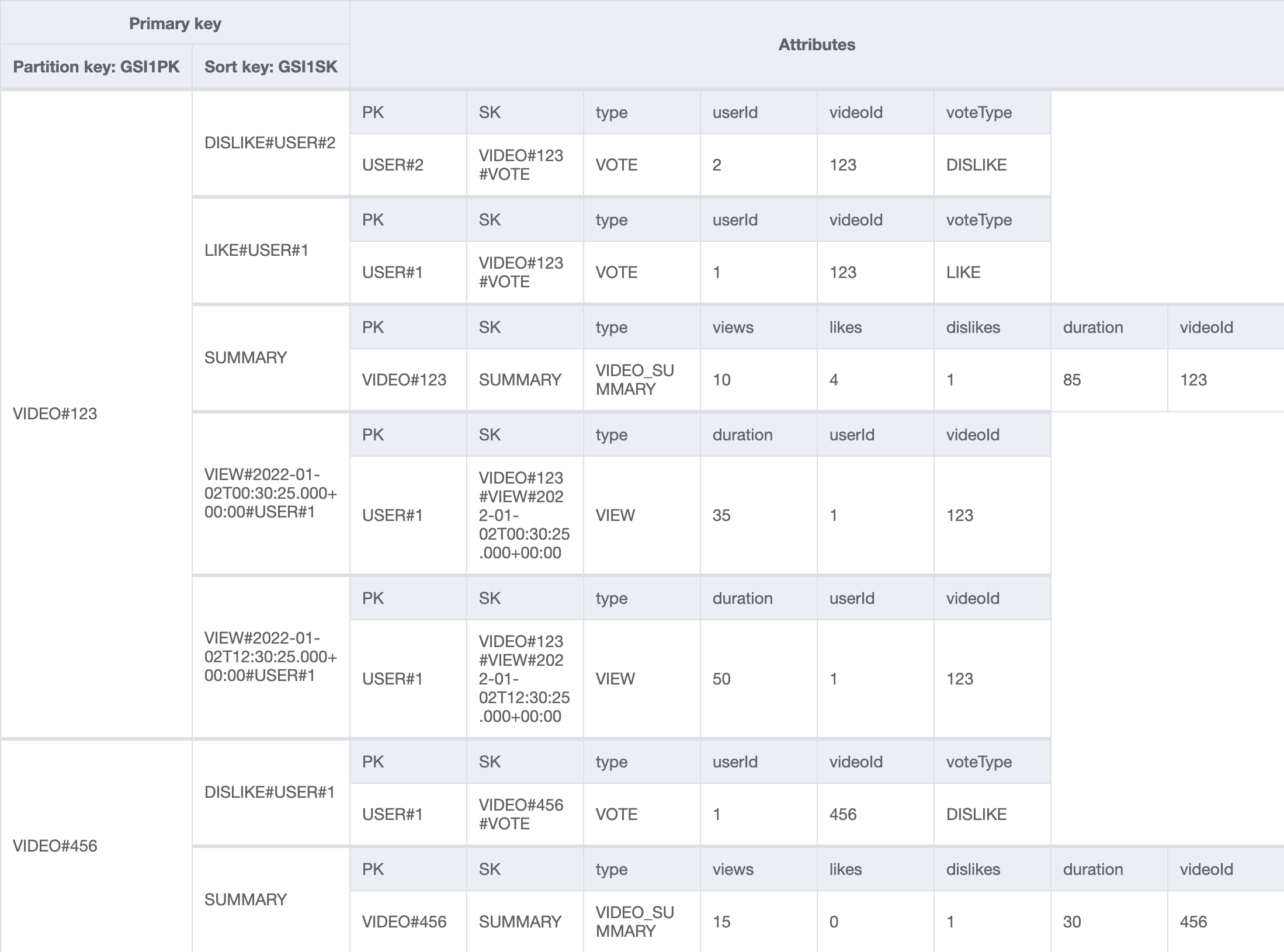

Let’s check out our data model for the platform. I’m using DynamoDB as the database and following the single table design paradigm here. If you want to learn more about that, check out my introduction to DynamoDB and the single table design pattern. The base table has a composite primary key made up of the partition (PK) and sort key (SK). There is also a global secondary index (GSI1) with the partition key GSI1PK and sort key GSI1SK. This allows us to lay out our data as follows:

This can be a bit overwhelming at first, but we’ll walk through it. In the base table, each user has their own item collection that’s identified by the key USER#<userId> and in that item collection, we first see the summary item that contains the aggregates for that user. Then we have different view items, each of which is identified by the video id it belongs to and when it was stored. That’s because we can watch videos multiple times: VIDEO#<videoId>#VIEW#<timestamp> . Each view item contains the duration in seconds as well.

Then there are also vote items that are identified by the video id: VIDEO#<videoId>#VOTE. The vote items contain the voteType that tells us if it’s a like or dislike. We don’t store a timestamp in the key, because we want to make sure there aren’t multiple likes or dislikes per video by a single user.

There is also an item collection for each video (VIDEO#<videoId>) that only contains the summary item with the statistics for the video. If we look at our global secondary index, we can see that the perspective changes. Here we can see the view and vote records per video in a single item collection.

This table layout allows for a variety of access patterns such as:

- Give me the statistics per videoId

- Give me the statistics per userId

- Give me all views per videoId

- Give me all likes per videoId

- Give me all dislikes per videoId

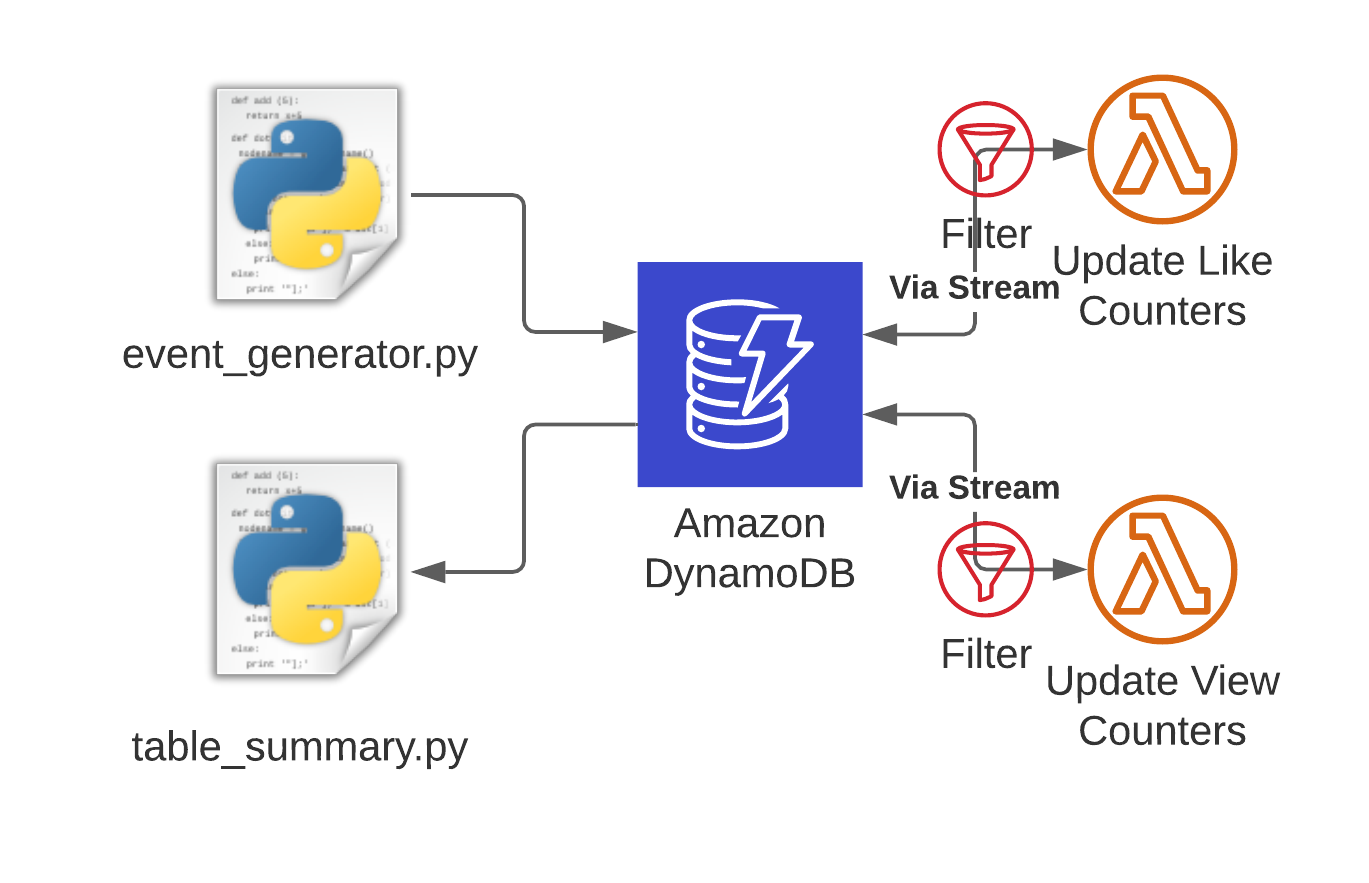

Now that we’ve talked about the data model, let’s see how we can create and update the aggregate records. Essentially whenever a new record of type VOTE is added to the table, we need to update the like and dislike counters on the video and user the record refers to. The same is true for new VIEW records. When the USER_SUMMARY or VIDEO_SUMMARY items are updated, we don’t need to do anything. I’ve provided some code on Github that implements this architecture if you want to follow along.

The code is a CDK app that creates a DynamoDB table with the required keys as well as two Lambda functions that update the like and view counters. Each Lambda function is connected with a filter to the DynamoDB stream and only responds to the relevant records. At the time of writing this, the higher level DynamoDB event source in the CDK doesn’t support the filter criteria parameter yet, so we create this filter through the lower level Event Source Mapping object:

# Filters aren't yet (CDK v2.3.0) supported for DynamoDB, we have to

# go to the low level CFN stuff here

_lambda.CfnEventSourceMapping(

self,

id="update-view-counters-event-source",

function_name=update_view_counters_lambda.function_name,

event_source_arn=data_table.table_stream_arn,

starting_position="LATEST",

batch_size=1,

filter_criteria={

"Filters": [

{

"Pattern": json.dumps({

# Only capture view events here

"dynamodb": {"NewImage": {"type": {"S": ["VIEW"]}}},

"eventName": ["INSERT","REMOVE"],

})

}

]

}

)

This is an example that captures only INSERT and REMOVE events from the stream if the record has VIEW as a value in the dynamodb.NewImage.type.S key. You can also do more advanced filters here, take a look at the docs for reference. There are also two python scripts that complete the demo. The event_generator.py generates random view and vote events and stores them in the table, while the table_summary.py periodically queries the user and video summaries and displays them in the console.

If you start the event generator, you’ll see something like this:

$ python3 event_generator.py

USER 0 likes VIDEO 5

USER 0 watches VIDEO 6

USER 2 watches VIDEO 2

USER 3 watches VIDEO 3

USER 4 dislikes VIDEO 9

USER 0 watches VIDEO 4

USER 0 likes VIDEO 8

Now start the table summary script in another tab and you’ll see the view and like/dislike counters change.

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|videoId |views |duration |likes |dislikes |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|0 |44 |3389 |5 |1 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|1 |40 |2985 |4 |2 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|2 |40 |3280 |4 |3 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

# [...]

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|9 |41 |3000 |3 |2 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

Fetched at 2022-01-02T17:05:29

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|userId |views |duration |likes |dislikes |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|0 |83 |6193 |9 |2 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|1 |85 |6002 |5 |6 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|2 |96 |7502 |9 |2 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|3 |71 |5283 |8 |4 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

|4 |88 |7009 |6 |7 |

|----------+----------+----------+----------+----------|

Fetched at 2022-01-02T17:05:29

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

One more nice thing besides the reduced number of needless invocations is that I can make more assumptions about the kind of data I’m getting in my Lambda functions:

def lambda_handler(event, context):

# We can work on the assumption that we only get items

# in NewImage with a type of "VIEW", that means we can

# rely on userId, videoId, and duration being present.

# We can also assume we get a single record.

item = event["Records"][0]["dynamodb"]["NewImage"]

event_name = event["Records"][0]["eventName"] # INSERT or REMOVE

user_id = item["userId"]["S"]

video_id = item["videoId"]["S"]

duration = item["duration"]["N"]

I encourage you to check out the code on Github and play around with it yourself. It’s a neat feature that doesn’t come at additional costs.

Summary

In this post we’ve taken a look at the new event filtering feature in Lambda and how it can be used to reduce cost through avoiding unnecessary invocations and simplify your code by allowing you to outsource your event filtering logic to AWS.

I hope you enjoyed the post and for any feedback, questions or concerns, feel free to reach out via the social media channels in my bio.