A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing - Hidden EC2 Permissions

During some R&D for a new blog post, I experimented with IAM conditions in Trust Policies. Some small mistakes during this led to instances that have limited privileges according to the AWS Web Console and CLI. But in reality, they can work with administrative permissions for a few hours - unnoticed.

Have I piqued your interest? Let’s see how to reproduce this effect then.

Probably everyone who works with AWS knows that you can assign IAM roles to EC2 instances. This mechanism enables them to work with the AWS API and avoids creating technical users.

The idea behind these roles is simple: provide automatically generated API credentials, which are only valid for a short time and rotate periodically. Essentially, an EC2 instance should never have access keys configured anywhere on its file system.

If you already went deeper into how AWS works internally, you know that the Instance Metadata Service (IMDS) provides the necessary mechanism for these short-lived credentials. It is usually reachable on a special, non-routed IP 169.254.169.254 (or fd00:ec2::254 if you are using IPv6)1 and provides everything over a convenient HTTPS interface. The most recent iteration is called IMDS version 2, although our example in this article will use IMDS version 1 to make following along easier2.

IAM roles consist of different parts like associated IAM permission policies (e.g., an AWS-managed policy like SupportAccess or your custom ones) and a trust policy. While most people know the first type of policy, the second one often causes some confusion.

Simply put, a trust policy states who is allowed to use the role. Examples include: users from a different account (account ARN), AWS services (service principals like ec2.amazonaws.com).

After we refreshed our memory on these basic concepts, how can we get to the issue I teased?

Create Simple Role and attach to Instance

First, let us create an IAM role for EC2, which grants us plenty of rights. For demonstration purposes we will use S3FullAccess in this post. We will replace this after boot with another policy to achieve the desired effect (see next section).

Now on to creating a demo instance - you probably have created countless EC2 instances already. So choose some OS image, an instance type, pass the new role we just created and make sure you can access the instance to play around with it.

You have your vanilla EC2 instance running with way too many permissions by the end of this.

Create an intentionally broken, least privilege policy

Now for the fun part. Remember the paragraph about trust policies? We will intentionally create a broken one and then use it to hide our privileges from prying eyes.

For my example, I created a new EC2 role with the SupportOnly policy assigned. While it would be strange to have a machine needing this, it is enough for our small demo.

On the “Trust relationships” tab of this new policy, start editing the trust relationship like this:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"Service": "ec2.amazonaws.com"

},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole",

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"iam:AssociatedResourceARN": "${ec2:SourceInstanceARN}"

}

}

}

]

}

The condition can be anything as long as it passes the validity check and contains a dynamic component like the ec2:SourceInstanceARN variable.

Why do we do this? To pass all AWS syntax checks but still create a role that cannot be assumed, as the condition never applies.

Hide Privileges

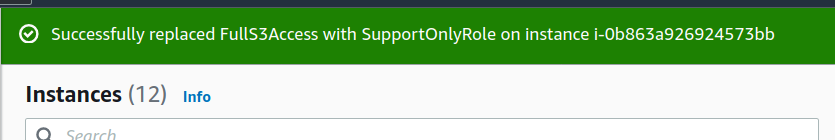

By now, you probably have an idea where we are going next: we will switch the EC2 role of our instance. This will work because the AWS Console cannot evaluate the condition beforehand:

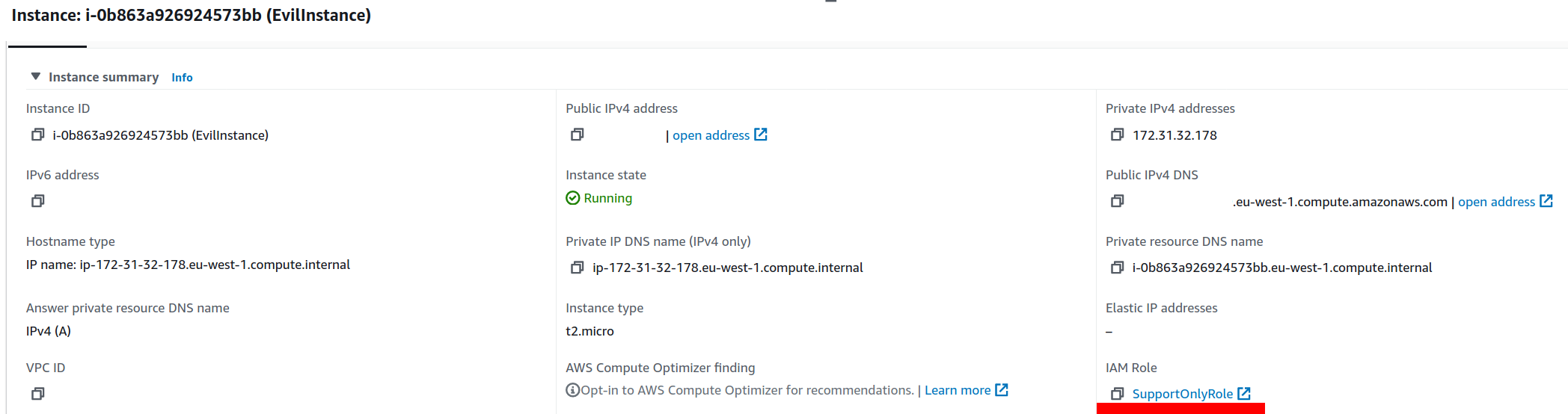

Now our instance shows a harmless role, both in the AWS Web Console and the CLI.

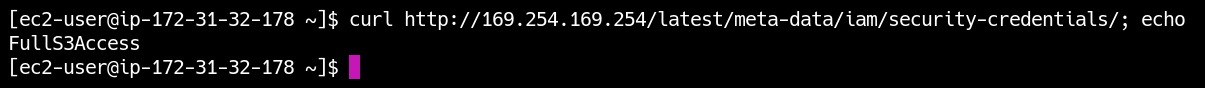

But if you connect to the instance now, you can check the assigned credentials via a curl command:

Surprise! The assigned role is still the old one, with extended privileges - despite the harmless one displayed by AWS. You can check its functionality by executing AWS CLI commands.

For the remaining duration of the session, which is about 6 hours, we can now use extended privileges. The only indication that something is wrong is a weird but plausible condition on the role’s trust policy.

Side Effects

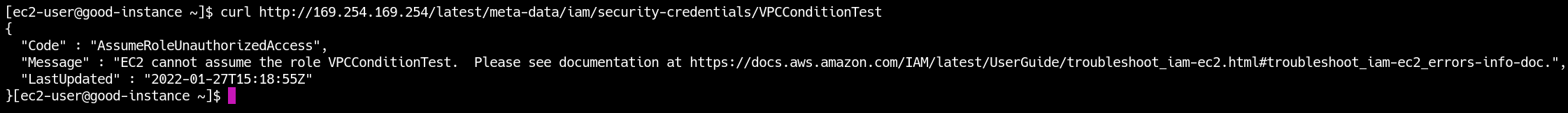

This technique seems to break something in IAM, though, as trying to switch to a different IAM role will only output a relatively obscure error message.

Also, after the expiry of the STS session, you will see an AssumeRoleUnauthorizedAccess message when trying to get the actual credentials.

Summary

So the steps are:

- Create instance and attach IAM role with elevated privileges (like

AdministratorAccess) - Create intentionally broken, new IAM role with harmless privileges (like

SupportOnly) - Attach broken policy to instance

- Work with elevated privileges for several hours, invisible to everyone (except CloudTrail)

All this is “by design”, as we have the separation between the AWS management plane, which assigns roles to instances (think of it as “compile time”), and the data plane that evaluates the policies (“run time”).

Assigning some non-assumable IAM roles will result in six hours of disparity between actual and shown permissions. You could revoke all sessions on the IAM role page, but this might have side effects, and you need to be aware of the issue in the first place.

To exploit this phenomenon, you would need broad IAM and EC2 permissions - and only get a temporary foothold in the account. From that perspective, the implicated additional risks seem rather low. You could also monitor your account for trust policies on EC2 roles which contain dynamic conditions. But in reality, you would probably noticed a compromise even before you detect a crafted IAM role like this.

I hope this was fun for you and see you next time!

Updated Febuary 4th 2022: Clearer wording and extended summary about resulting risks. Thanks Patrick!

References

-

Find more about this in my old blog post on these APIPA/ULA addresses (German) ↩︎

-

The old IMDSv1 makes stealing credentials too easy if your application unsafely processes user requests via Server-side request forgery (SSRF). ↩︎